It’s been quite some time since I’ve made one of my weekly posts, but as Sunday is reading day, this seemed to be a good place to start.

Each week, I devote part of my Sunday to reading. I tend to accumulate a lot of saved links on Facebook during the week, and I like to try to keep up with what fellow writers are posting here on WordPress. At the end of my reading day, I like to put up a post to draw my readers’ attention to a few articles I found to be of particular interest.

Here’s what I enjoyed today:

Who’s the First Person in History Who’s Name We Know?

by Robert Krulwich, National Geographic

Originally posted in Krulwich’s running blog on Nat Geo’s website, Curiosity Krulwich in 2015, this was a mesmerizing read.

For those who take an interest in history, there are always odd, unanswered questions regarding firsts. Who invented the first writing system? The first numbers? Of course, it’s safe to say many of these questions will never be answered to our satisfaction; after all, history is the study of written records. No doubt our distant ancestors living in caves had names, if only to differentiate one human from another (“Hey you!” is a trifle ambiguous). But if any of these ancient people had a means of expressing their identity visually, they took the means to understand it with them.

In the article, Krulwich explores this question, and in doing so challenges our perceived notions on history while providing a commentary of sorts on the basis of our civilization. For the record, the Sumerians were the first civilization on Earth with a standard form of writing (to the best of our knowledge), meaning they would be the first people in history to provide names. And the earliest name we’ve found was not the name of a king, or a high priest, or even a warrior. The first named person in history, as far as we can tell, was effectively an accountant.

Exhibition to Bring Winslow Homer’s Long-Lost Camera – and His Photography – into Focus

by Julissa Treviño, Smithsonian.com

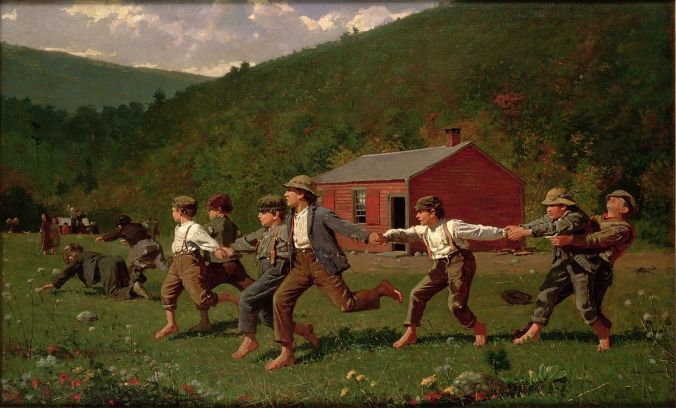

I found this one of personal interest. Winslow Homer is widely known as one of the foremost American painters. Arguably his best-known work, Snap the Whip, is displayed at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, not far from where I grew up. My grandmother once worked as a docent there.

Snap the Whip by Winslow Homer, oil on canvas, from the Butler Institute of American Art

While Homer is best known for his painting, few are familiar with his photography. Curators at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine, hope to change that this summer with a new exhibition.

Though the exhibition will feature several paintings by Homer and 50 of his photographs, arguably the showpiece of the exhibit will be Homer’s camera, recently recovered from a man living near Prouts Neck, Maine: a place Homer once called home. Originally procured in 2014, the camera took time to authenticate, but ultimately proved genuine. Though the camera itself, produced in England by Mawson and Swan, is a fascinating piece, perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the exhibition is the relationship between Homer’s photography and his painting. Though Homer seldom discussed his photography, art experts believe it heavily influenced his style of painting.

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Earth’s Past Climates

by Rachel E. Gross, Smithsonian.com

It’s safe to say that climate science is all the rage right now. And with good reason: thanks to scientific modeling and earth studies, we’ve at least reached the point where, regardless of one’s political persuasion, most generally agree that Earth’s climate is indeed changing, regardless of what, precisely, is driving that change. But how, exactly, do scientists produce detailed models of Earth’s past climates?

In this detailed yet digestible article, Gross guides the reader through the complex process by which climate scientists reconstruct paleoclimates. Through the use of a wide range of physical records, from tree rings to Antarctic ice cores to the layers of extinct lifeforms’ teeth, climate scientists are able to weave threads together to produce a comprehensive snapshot of climate on Earth hundreds, thousands, even millions of years ago. The further back in Earth’s history we look, the more sparse our data becomes, but through ingenuity and creativity we’ve been able to find bits of our planet’s story in the most remarkable places.

Of course, as Gross points out, the resulting models aren’t perfect, but few things in science truly are. And a model needn’t be perfect to expand our knowledge of Earth’s past…or inform our understanding of its future. As Gross remarks, “To know where you’re going, you have to know where you’ve been.” Climate models may not tell us how to solve the problems we face, but they may provide a better idea of what might happen if we don’t.

Knowledge is power. Take time out to read a bit every day. It’s your window into the world around you.