July 20, 1969 was the day everyone watched television. Roughly twenty percent of Earth’s population sat in front of a screen that night, watching something impossible. Far away, on the surface of another world, humans were taking their first steps. Through a grainy feed, transmitted across the cosmic dark, they watched as man took the next step in his conquest of the heavens.

It was a defining moment in human history; one of those moments where everyone remembers exactly where they were, what they were doing when it happened. It was a moment that proved we could do anything. It showed what we could do when large numbers of humans worked together toward a goal, motivated not by profit or self-interest, but by loftier principles: to explore, to study, to rise to a challenge. To know.

The Apollo missions were the crowning achievement of both the US space program and humanity’s exploration of space; a feat thus far unequaled. And as such, a lot of time and work went into making that moment happen. There were trials and tribulations, setbacks, failures and heartbreak. There were arguments. There were moments of doubt. Not everyone got the credit they deserved. Good men died.

But through it all, mankind persevered, and ultimately, we grew a little. Through the hard work and dedication of people like physicist Katherine Johnson, pioneering computer programmer Dorothy Vaughan, and engineer Mary Jackson, through the sacrifice of men like the crew of Apollo 1: Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, through the vision and brilliance of men like Dr. Werhner von Braun, and finally through the bravery of the Apollo 11 crew: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, humanity took a tremendous step forward. With each lurch ahead, from the Mercury Program to Gemini and finally Apollo, we learned to run by stepping into the footprints left by those that came before, until the final set lay undisturbed on the lunar surface.

It has been fifty years since Neil Armstrong took his small step onto the moon. Space travel has continued on, and now we stand poised for yet another surge of discovery. Already, we have accomplished a great deal since those early days. Since Apollo 11, humans have begun the conquest of space in earnest…

-Apollo 11 became the first of seven lunar exploration missions launched by NASA from 1969-72. Only one of those, Apollo 13, failed to land on the moon. While Armstrong was the first man to walk on the moon, to date the last has been Eugene Cernan, mission commander of Apollo 17.

-After the Apollo Program ended, four of the remaining command modules were used to ferry crews to Skylab, the first US space station, launched in 1973. From 1973-74, four crews were launched to the orbiting laboratory, conducting vital research and testing new technologies designed to allow astronauts to live in space for prolonged periods. The longest of these missions, Skylab 4, lasted eighty-four days.

-In 1975, the final Apollo command module was used for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. During the mission, the module docked with a Soviet Soyuz 19 command module using a specially-designed docking adapter. The mission marked the effective end of the Space Race, and began the US-Russian space partnership that has driven human space exploration ever since.

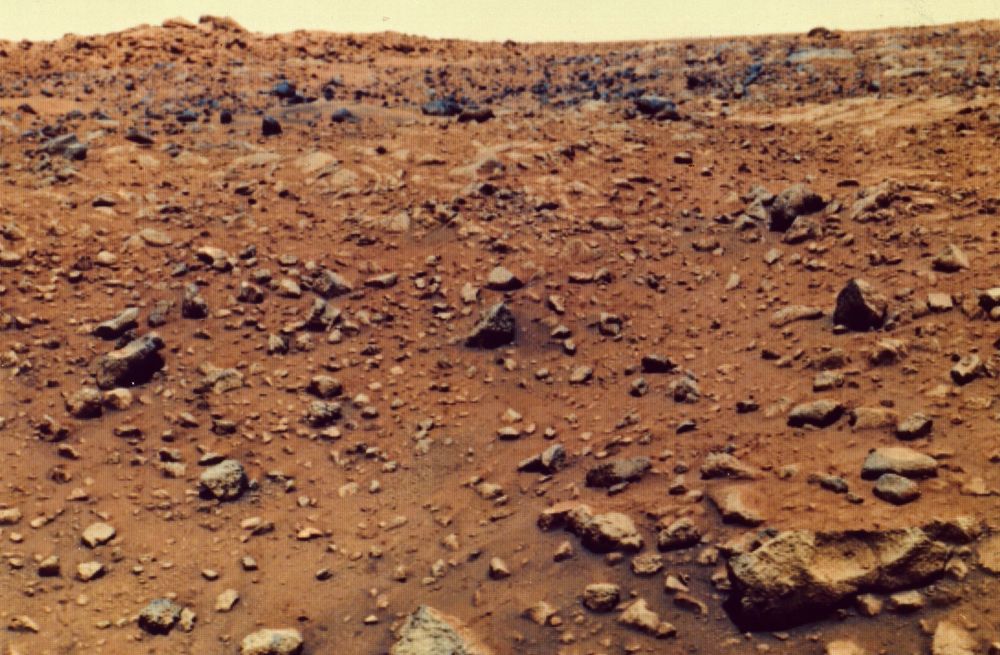

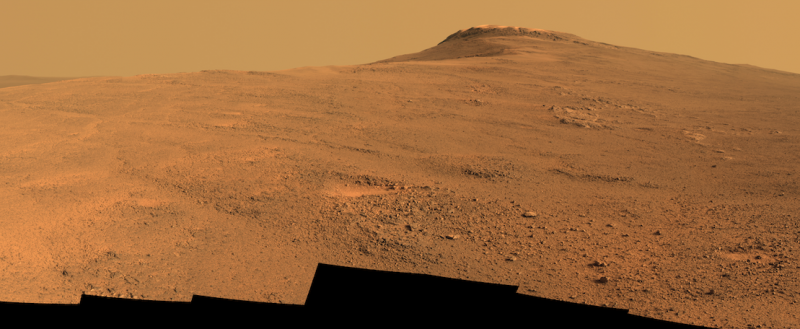

-In 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 probe successfully touched down on the surface of Mars, becoming the first of two probes to offer us our first glimpses of the Martian landscape. Viking 1 continued transmitting for over six years, a record for a Martian mission that would not be broken until 2010.

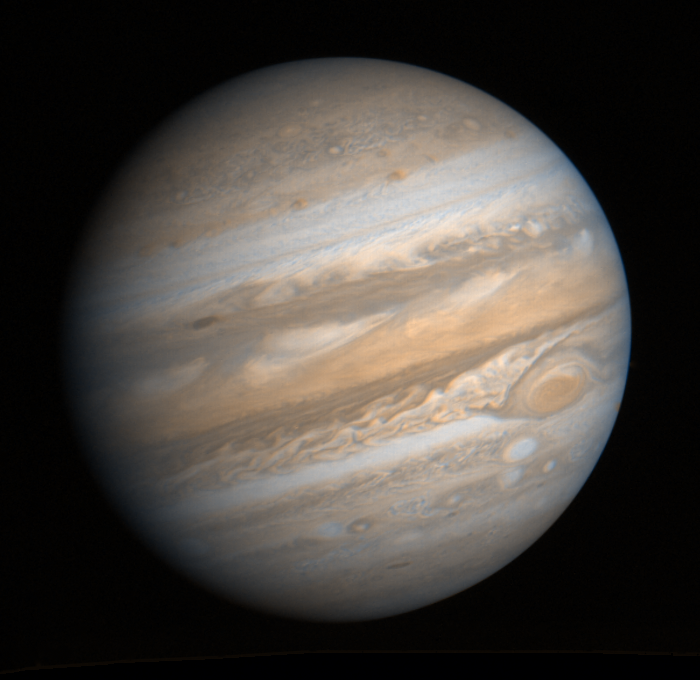

-In 1979, the Voyager 1 space probe began its study of Jupiter. Launched in 1977, the two Voyager probes became the first human-built objects to visit the outer planets, returning our first clear images of the outer solar system. Voyager 1 continued to study Jupiter and Saturn, while Voyager 2 continued on to Uranus and Neptune. The Voyager 2 probe has since left our solar system entirely, and entered interstellar space.

-On April 12, 1981, NASA launched STS-1, the first mission of the space shuttle Columbia, which began the US Space Shuttle Program. Unlike previous spacecraft, the shuttle was reusable, capable of being launched into space as a rocket and landing as an aircraft. The Space Shuttle served as NASA’s primary launch vehicle from 1981 to 2011, conducting experiments in orbit and later serving as a crew and equipment transfer vehicle, first for the Russian Mir space station and later the International Space Station.

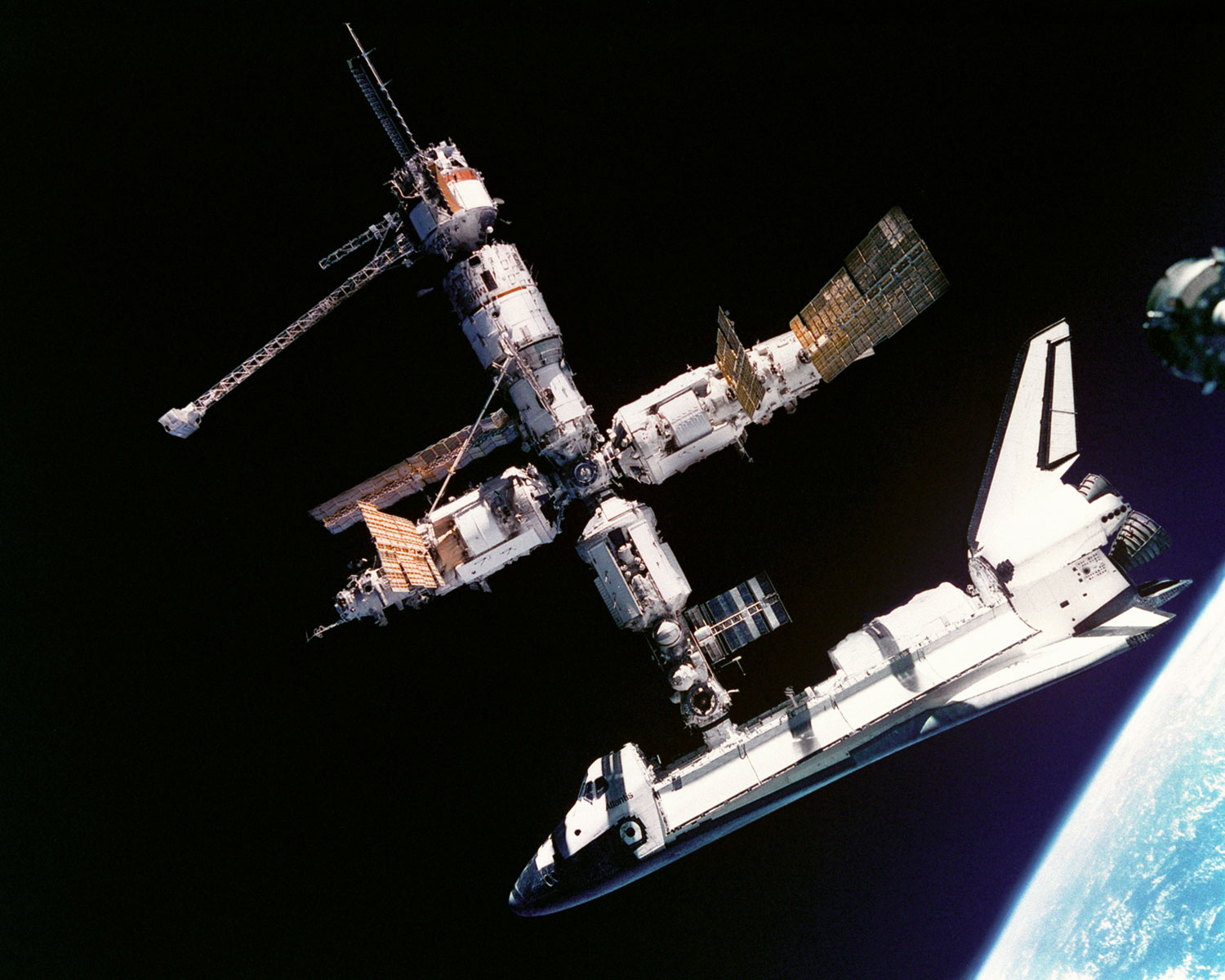

-In 1995, the space shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian Mir space station, becoming the first US spacecraft to dock with a Russian spacecraft since the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975. The mission, STS-74, marked the beginning of the Shuttle-Mir Program, and joint operations of the US and Russian space programs, which continues to this day.

-In 1997, NASA’s Mars Pathfinder probe touched down on Mars, becoming the first spacecraft to do so since the Viking missions. In addition to conducting numerous observations and analyses of the Martian surface and atmosphere, the probe also launched a tiny rover, Sojourner. While the rover only traveled a total of 100 meters, it served as a vital test bed for technologies that later missions would rely on.

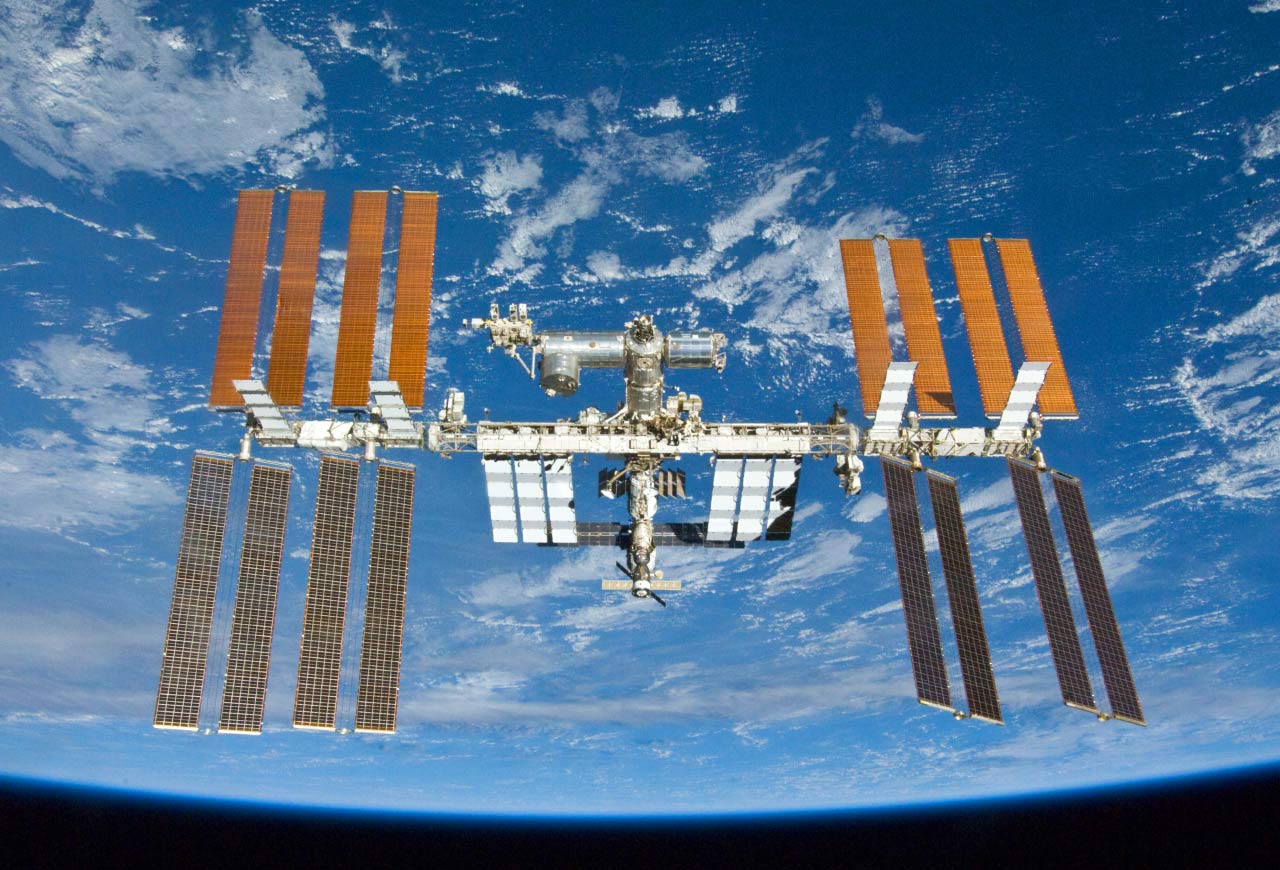

-In December of 1998, a US-built connector node was successfully mated with a Russian cargo module, effectively beginning the assembly of the International Space Station. The station’s first crew, Expedition 1, arrived nearly two years later aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Since then, the ISS has been continuously inhabited, leading thus far to the Expedition 60 crew, which arrived last month. All told, astronauts from ten nations have served aboard the ISS, which by the end of principal construction in 2011 covered roughly two acres in space. The ISS mission is ongoing, and expected to continue well into the 2020s, and possibly beyond.

-In 2004, NASA landed a pair of rovers, named Spirit and Opportunity, on the surface of Mars. Far larger and more sophisticated than the earlier Sojourner rover, the new rovers were conceived as the first in a series of reconnaissance missions, intended both to learn more about the geological composition and history of Mars as well as lay the groundwork for future manned missions. The rovers’ missions were intended to last a total of ninety Earth days; however, the Opportunity rover continued exploring the martian surface until 2018, setting a mission record at roughly fifteen years.

-On February 27, 2004, the Cassini-Huygens space probe arrived at Saturn. Launched in 1997, the spacecraft was intended to spend four years investigating Saturn and its vast system of moons. Ultimately, the mission was extended twice, continuing until 2017. During the mission, Cassini substantially increased our understanding of the second-largest planet in our solar system, discovering new moons and returning breathtaking images of the planet.

In 2005, the Huygens probe separated from Cassini, and touched down on the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The spacecraft returned images from the surface, showing the moon to be covered in lakes and seas of liquid methane.

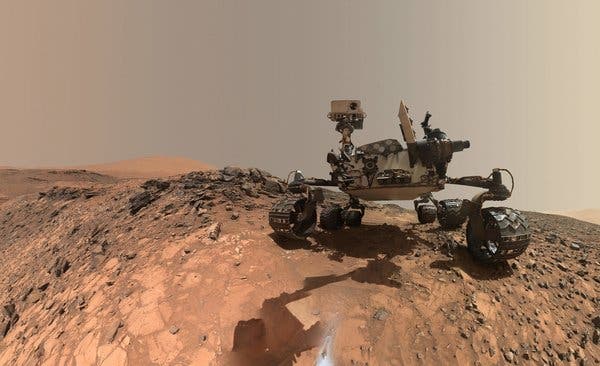

-In 2012, NASA’s Curiosity rover touched down on Mars. Far larger and more sophisticated than Spirit and Opportunity (which remained active upon its arrival), the rover was intended to analyze martian soil for organic compounds as well as assess surface conditions, including radiation levels, which could affect future manned missions. Since its arrival on the planet, Curiousity has made a series of major discoveries, including finding organic molecules in martian soil and discovering evidence of liquid water. The Curiosity mission is ongoing, having been extended indefinitely.

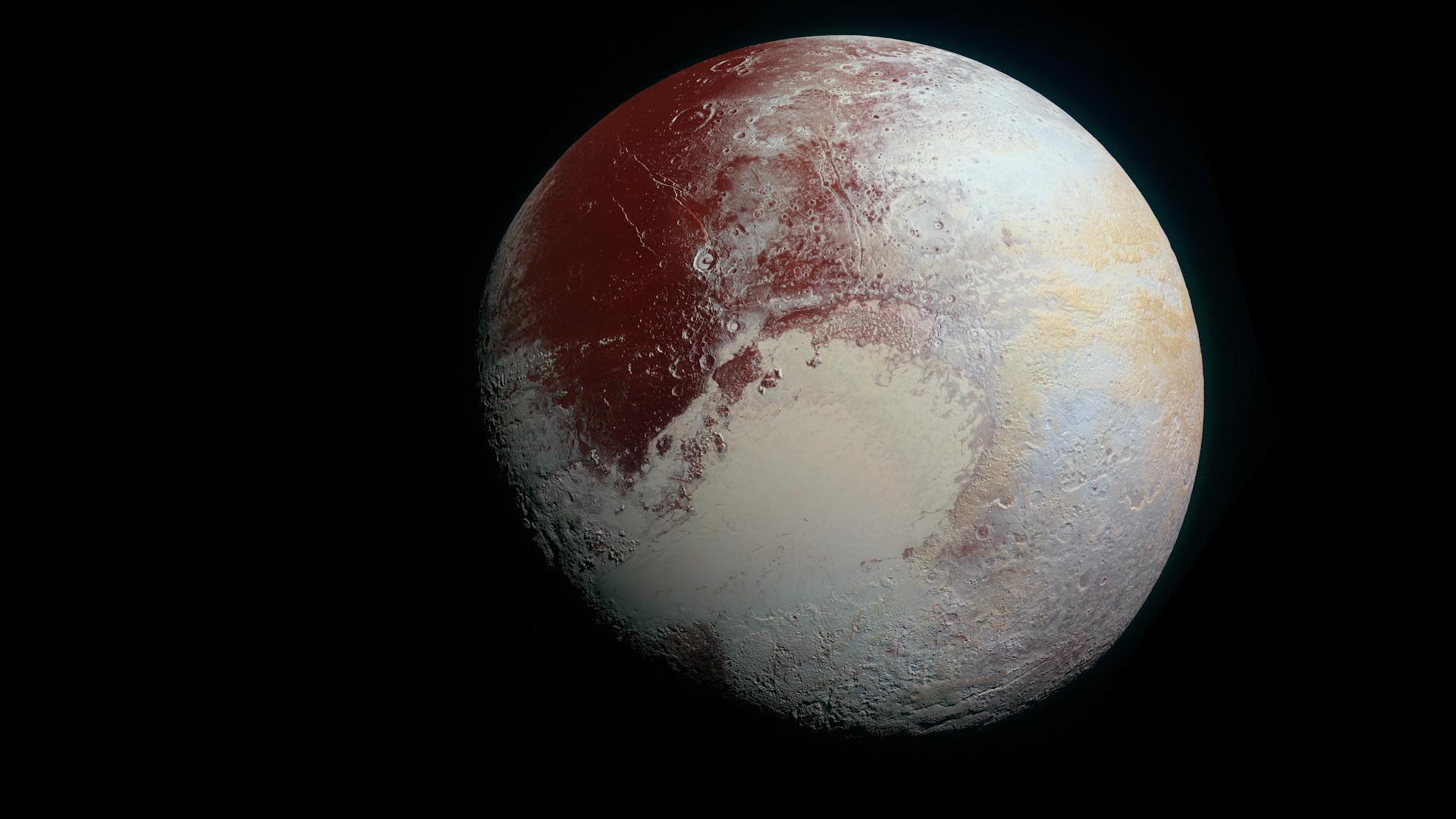

-In 2015, NASA’s New Horizons probe reached Pluto. Launched in 2006, the probe succeeded in beaming back humanity’s first clear images of the dwarf planet (previously, the Hubble Space Telescope had attempted to take an image of Pluto). The New Horizons mission is ongoing, with NASA planning to use the spacecraft to continue exploring the Kuiper Belt well into the next decade.

Our story in space is far from over. Even now, NASA planners and engineers are hard at work, preparing for manned missions to the moon and Mars. Right now, the Artemis Program is preparing for new lunar missions, including the construction of the Lunar Gateway: a permanently-inhabited space station in orbit of the moon. We have come far, though we still have a long way to go.

As for Apollo 11, Tranquility Base has lain undisturbed for five decades, a monument to human ingenuity, tenacity, resilience, and triumph. Those responsible for the mission, not only the three brave men who traveled to the moon but the many men and women who made it happen, stand as heroes, a credit to our species. In time, Tranquility base will continue to fade; the flag will be bleached by the sun, reflective material will flake away from the lunar module. Ultimately, the trappings of nations and factions that adorned the site will be lost. But the bootprints will remain: a sign of footsteps long past, showing only that humans once walked this barren place. As such, the most important message we could leave will remain forever:

“We were here.”