In space exploration, interstellar travel is the ultimate goal. We’ve yet to fully explore our own solar system, but those who are driving us into space are a forward-thinking bunch. And while our system offers vast wonders, there’s a whole galaxy of stars and planets out there, just waiting for us to see them up close. But getting there is no small feat.

At present, we are confined to our little star system, the closest stars comfortably beyond our reach. Even with the best technology available to us right now, a trip to Proxima Centauri would take decades. And that’s just the nearest star system to us. Beyond that, trips at sublight speeds would be measured in centuries, if not millennia.

This means, realistically, to become a true spacefaring species we must learn to break what was once viewed as the most unbreakable rule of the cosmos: the universal speed limit. Einstein made it clear: to travel at the speed of light would require an infinite amount of energy. Thus, traveling that fast, much less any faster, is impossible. Period. But while Einstein was a brilliant man, we’ve learned a lot since his time. Including the tantalizing reality that, while the laws of physics cannot be broken, they can be bent, nearly to the point of breaking. Thus, in a matter of decades FTL travel has gone from being impossible to inevitable. And given the current state of research, just as Chuck Yeager famously broke the sound barrier, no doubt one day a lucky human will have the distinction of breaking the light barrier as well.

So let’s take a look at our current understanding of faster-than-light travel, and what it means for sci-fi writers.

FTL and Science Fiction

It’s almost not worth noting that, in sci-fi, travel faster than the speed of light has become a staple. The first well-known form of sci-fi FTL was the “warp drive” featured on Star Trek. While Gene Roddenberry was a visionary filmmaker, warp drive was largely dismissed by scientists in the 1960s as being completely unfeasible. Yet, in 1994, an obscure Mexican physicist named Miguel Alcubierre published a groundbreaking paper in which he showed that warp drive as depicted in Star Trek was, in fact, possible, without violating general relativity. Suddenly, warp drive went from being the least-possible form of FTL propulsion to quite possibly the most practical.

Since then, warp drive has been vaulted into the realm of accepted science. NASA has become a leading partner in the 100 Year Starship initiative, spearheaded by former astronaut Mae Jemison, with the audacious goal of developing a working Alcubierre drive within the next century.

For the sci-fi writer, FTL can be problematic. It’s so common in science fiction that its use has become an accepted trope. As such, it can be difficult to sell to the more discerning sci-fi reader of today. So let’s take a look at a few of the best-known theoretical forms of faster-than-light travel, how they might work, and how to depict them believably in fiction.

Warp Drive

Seen through the lens of modern science, Star Trek‘s warp drive is just one of the many aspects of the series that displays Gene Roddenberry’s uncanny grasp of science and the future of mankind. And we have Miguel Alcubierre to thank for filling in many of the practical aspects of the design.

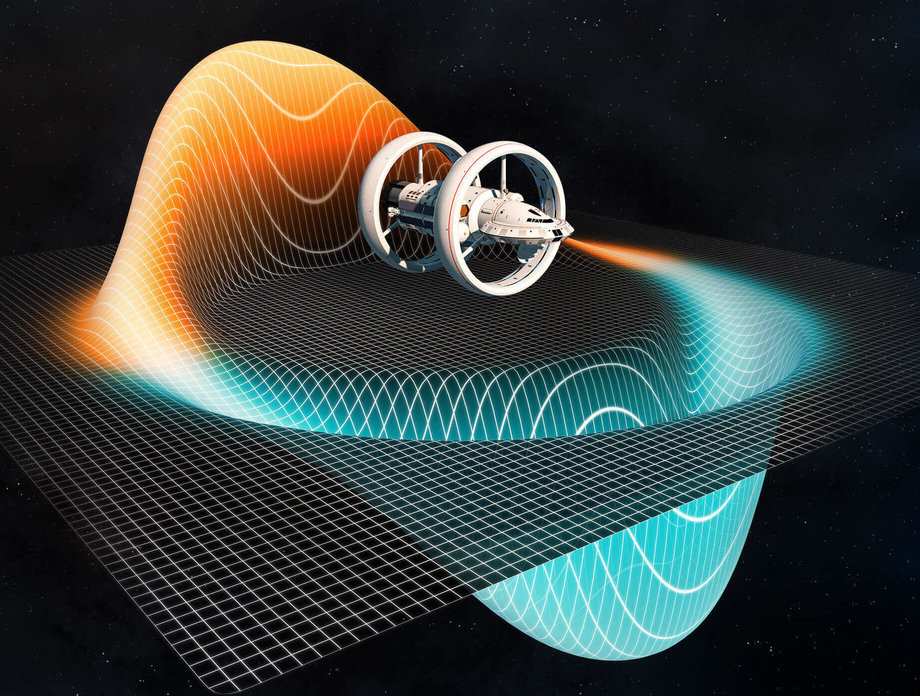

Essentially, a warp drive operates by using exotic matter or Casimir plates to create a field of negative mass. This field is projected outward from the spacecraft, creating a “warp bubble” that isolates the surrounding spacetime. By stretching the space behind the craft while compressing space ahead of it, the vehicle is capable of moving at speeds faster than light. This sounds fanciful, but the drive obeys the law of general relativity, because the spacecraft itself remains stationary, while the space around it moves.

While Star Trek got a lot right, it got a few key aspects of warp travel wrong. The first, and least crucial, is what the crew of a spacecraft would see. While the view of elongated stars whizzing past makes for great television, in reality the crew would see nothing. This is because at such speeds a runaway doppler effect would produce a constant blur of garish white light. The light might be so bright as to be blinding.

The second is the practical use of the drive. The good news is that recent research has shown the amount of energy required to operate a warp drive is not insurmountable. The bad news is that it is still immense, far more than any practical form of power generation we have could meet. There’s also the problem of travel time. While Star Trek often showed starships traveling at warp for days or weeks, in reality a trip by warp spacecraft would likely still be measured in years. Consider this: let’s say a warp-capable spacecraft could travel at a relative velocity of about ten times the speed of light. That’s very, very fast. But Vega lies roughly 25 light years from Earth. That means such a spacecraft would still take two and a half years to get to Vega. And Vega is one of the closest stars to Earth.

Space-Folding Drive

Another common theoretical system used in science fiction, a space-folding drive operates by utilizing one of the more bizarre features of the standard model: wormholes.

In physics, a wormhole is a theoretical object consisting of two singularities. These two singularities are pinched inward, until they eventually touch, forming an Einstein-Rosen bridge. Such a singularity would theoretically be traversable, allowing rapid travel between two points in space and time. Potentially, a spacecraft entering a wormhole could arrive at the other end before it entered.

Let’s start with a few common misconceptions:

1. A Wormhole isn’t a “hole”…

…at least not as we might perceive it. The first notable work of science fiction to get this one right was Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. As a wormhole is a four-dimensional object, the actual aperture would not be visible to humans, who see only in three dimensions. It would be akin to viewing a three-dimensional object from only one side: one cannot see the other side, and thus has no idea precisely what shape one is looking at. The only aspect of a wormhole visible to human observers would be the extreme lensing effect produced by its immense gravity. Thus, a wormhole would appear to be spherical.

2. Wormholes are not naturally occurring phenomena

To the best of our knowledge, we cannot simply go out and find a wormhole. We would have to create one. The science on creating a stable wormhole is far less well-established than that of the warp drive. Most likely, a spacecraft would have to be capable of producing a stream of antigravitons (assuming they exist).

So, what would the crew of a space-folding vessel witness as they passed through a wormhole? Amazingly, science has an answer, at least based on our current understanding of astrophysics.

Upon crossing the event horizon, there would be a flash. During this flash, an individual would witness every event that had occurred anywhere in the universe up to that point. How the human mind would process this experience is unknown. Once inside the singularity, the crew’s vision would be obscured by the intense gravitational lensing: the view around them would twist and skew, with light seeming to swirl toward some unseen vortex: the point singularity, which would be invisible to them. Eventually, the spacecraft would reach the point at which the two singularities touch. At this point, there would be a second flash, in which they would witness every event that would occur anywhere in the universe from that point until the end of time. Again, how the human mind would process this experience is unknown. After the second flash, the spacecraft would pass from the first singularity to the second. After passing through the second singularity, there would be a third flash, and the crew would find themselves at their destination.

One thing is certain: to make science fiction work, at least in the modern sense, employing FTL technology of some kind is crucial. But doing it right can avoid falling into common tropes, and help a sci-fi writer stand out in a crowd. After all, nothing science fiction has yet produced is as wondrous as the true science behind it.

Wow. This was a lovely post. I love space, though I don’t know much about it. And when I come across posts like this, I devour it all up. So thanks, Michael!

LikeLike