Of the four fundamental forces in our universe, the weakest of these may be the most recognizable. It’s an interaction between matter and energy, compelling mass to clump together. It forms a pull; one that binds our universe, producing everything from upright locomotion to the orbits of the planets and the structure of spectacular spiral galaxies. And it may also be the most crucial force in space travel, affecting everything from the course of the vehicle to the crew’s long term health.

As I often say, in space travel everything comes down to mass. Part of the reason for that is gravity. It affects everything, and for the modern sci-fi writer it’s a constant concern. Arguably the most universal McGuffin in science fiction is artificial gravity. As such, like many sci-fi tropes, it’s easy to do but hard to do right. So let’s take a look at gravity from the perspective of the science fiction writer: how to deal with its absence, and how one might produce it in space.

Artificial Gravity and Microgravity in Science Fiction

As previously stated, artificial gravity has long been a staple of science fiction. This is especially true in film and television, for an obvious practical reason: having artificial gravity makes filming easier. It negates the need for expensive, dangerous (and often unconvincing) flight harnesses. As such, since the early days of Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, and Star Wars, artificial gravity has gone hand-in-hand with sci-fi. The method varies, as does the degree to which writers bother to explain it. Star Trek featured “gravity plating”, which produced a field keeping everyone’s feet firmly on the decks. Star Wars was perhaps the most fast-and-loose with it, to the point where ships with no power still somehow had gravity aboard.

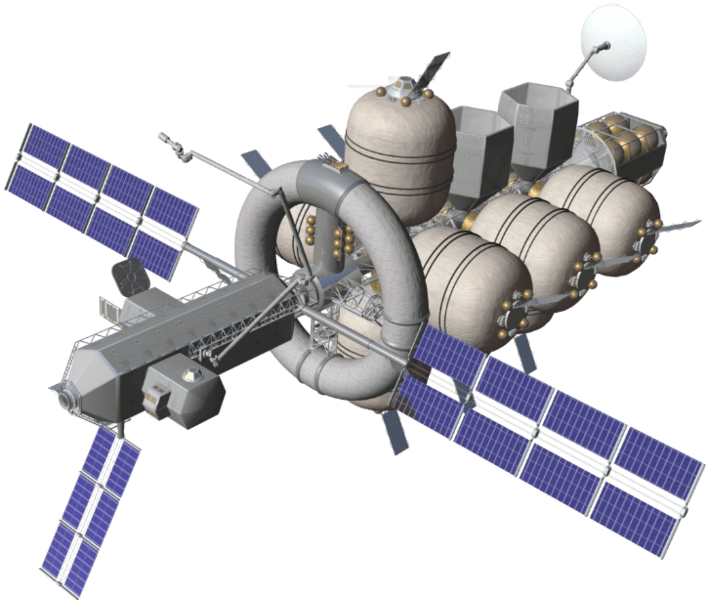

Arguably the most realistic fictional depiction of gravity onscreen to date came from Babylon 5. Babylon 5 featured extensive use of spin gravity: the practice of using a massive centrifuge to simulate the effects of gravity. On the show, ships from Earth often featured massive, spinning gravity wheels, allowing the crew to spend at least part of their time in simulated gravity, while much of the ship’s internal space remained a microgravity environment. The show went so far as to feature at least one Earth ship without gravity, noting that crews of such vessels were routinely rotated, so as to negate the long-term effects of microgravity.

So, how, exactly, does microgravity affect space travel?

The Effects of Microgravity

It should first be noted that “zero gravity” is a misconception. In any proximity to any large celestial body, gravity remains, albeit in a heavily-diminished form. Science refers to this as microgravity, and it is in this state that crews aboard spacecraft and space stations live their lives. For comparison, a quarter falling from a distance of about five feet will take roughly three seconds to hit the floor. On the International Space Station, it would take five minutes.

Microgravity has strange effects on things. Carrots grown in microgravity will grow in a U-shape, initially growing downward before realizing there’s no gravity to stop them. A flame will burn in a sphere, smoke gathering evenly before eventually snuffing it out. But for the purposes of space travel, most important is the effect on the human body. On Earth, blood pools in the legs due to gravity, forcing the heart to pump harder to keep it circulating. In microgravity, blood disperses through the body evenly, reaching equilibrium, which can lead to temporary dizziness. The fluids of the eye are affected as well, sometimes causing blurred vision, as are the fluids of the inner ear, causing vertigo.

In prologued weightlessness, the body languishes due to lack of gravitational resistance. Muscles atrophy, bone density is lost. The heart, no longer needing to pump hard to circulate blood, weakens. Spend enough time in microgravity, and one will be unable to return to Earth. The body simply won’t be able to take the strain.

In a microgravity environment, anything will float, or at least appear to. Hair flows freely; as such, astronauts with long hair tend to pull their hair into a bun or ponytail to keep it out of their eyes. Any equipment must be stowed securely, lest it float aimlessly through the spacecraft. Astronauts also sleep in bags affixed to the walls, and vacuum the water off their bodies after they bathe. Perhaps most importantly, there is no up or down in space. Thus, equipment is usually stored on every surface, as it’s impossible to pinpoint what would be the “ceiling” and the “floor”.

As stated, however, long-term exposure to microgravity has deleterious effects on the human body. Astronauts on prolonged space missions are required to exercise for at least two and a half hours a day. This helps to mitigate loss of bone and muscle mass, but in the long term the effects are inescapable. As such, it’s generally assumed that some manner of artificial gravity will be required for long-duration interplanetary missions, should the crew ever hope to return to life on Earth.

So, how does one produce gravity in space?

Spin “Gravity”

The simplest known method of producing, or at least simulating, gravity in space is the oldest: spin gravity. The idea of spinning a wheel to simulate gravity through centrifuge force existed as early as 1923, when German physicist Hermann Oberth floated the idea of a wheeled space station in his book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (“The Rocket into Planetary Space”). The concept is simple: when a hollow ring is spun, forces acting on objects within will resolve to press said object into the outer surface of the tube. Thus, humans within such an object would feel as though they were experiencing gravity, and their bodies would respond likewise.

The concept of simulated spin gravity has appeared frequently since the 1950s, notably championed by Oberth’s protégé Wernher von Braun. It has also appeared frequently in science fiction, from 2001: A Space Odyssey (which featured a two-wheeled station) and Babylon 5 and Interstellar (both of which featured a drum-shaped space station known as a Bernal Cylinder). Spin gravity presents numerous advantages, the most notable of which being that it’s possible with our current level of technology and understanding of physics. Such a system would be energy-efficient; as objects in space remain in motion unless a counter-force is applied, a gravity ring need only be set to spinning at the appropriate velocity, and it would spin indefinitely. However, it’s important for sci-fi writing purposes to note that all but the largest gravity wheels would have to spin rapidly to simulate Earth gravity.

Theoretical Models

Many sci-fi properties, most notably Star Trek, have featured a more extreme form of artificial gravity. These designs rely on the capability to generate gravitons: subatomic particles responsible for producing gravitational force. There is one major flaw in this idea: at present, the graviton is not definitively known to exist. The existence of gravitons is widely assumed, and recent experiments detecting gravity waves offer hope that the graviton will, one day, be discovered. For now, however, the existence of the graviton is merely inferred due to the existence of other subatomic particles (notably photons) responsible for energetic interactions in the cosmos.

In space, gravity is literally inescapable. And rest assured, when we do take our tentative first steps into the greater universe, we’ll need a way to keep everyone standing upright. As to what we employ to make that happen, for now that’s where science fiction writers come in. – MK

Pingback: From A to B | Writing Tomorrow