Science fiction thrives on strange, new worlds. Every great sci-fi story starts on a cool planet populated by alien life forms. From Vulcan to Naboo, science fiction has produced some incredible worlds. But there’s one thing we don’t talk as much about that plays an outsized role in the nature of planets: their suns.

While Star Trek and Star Wars had their heydays in an era when the very existence of alien planets was theoretical, we know today that planets likely vastly outnumber the stars themselves. And we’re learning more and more about how the nature of a star affects its planetary systems. So, in this new installment of “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a look at stars: how they’ve been depicted in past science fiction, and what our current understanding tells the modern sci-fi writer about how they sculpt the worlds in their orbits.

Stars in Science Fiction

Again, science fiction has often paid lip service to the affect stars have on their planets. But that’s not to say no one has ever said anything. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, stated that the planet Vulcan orbited the star 40 Eridani A, which is now known to possess a planetary system. Perhaps the most notable example of stars in science fiction comes from Star Wars. In Episode IV, George Lucas gave science fiction one of its most enduring scenes, as Luke Skywalker watched twin suns set over his home planet of Tatooine. It’s worth noting, based on current science, that the two stars of Tatooine’s system are likely an F-type primary and a K-dwarf companion.

Stars in Science

Before we dive into the science of all this, it’s important to remember that this is a rapidly evolving field. We’re still learning about the affect stars have on their planetary systems. But we’ve already learned a lot. First, let’s take a look at the main spectral classes, and what planetary systems they might harbor. To begin, a very brief explainer:

Our current classification system rates stars on color spectrum first, followed by luminosity. Thus, stars are primarily categorized by their spectral type (basically, their temperature) rather than their size. For our purposes, we’ll stick with the most basic classification system: spectral types.

Spectral Type M: Red Dwarf

Small and cool type-M stars, often called red dwarfs or M-dwarfs, are believed to be the most common stars in our galaxy, and likely the universe. The vast majority of stars in Earth’s close vicinity are M-dwarfs. However, while more distant stars like Sirius and Rasalhague have been observed for millennia, many of the nearby M-dwarfs were discovered recently, most during the 20th century. This is because, while they may be very close to us, they are very dim and very, very small.

Compared to our sun, most M-dwarfs are tiny, some only slightly larger than Jupiter. They emit significantly less solar radiation, which not only makes them hard to spot, but also means the habitable zone around the stars (the region in which temperatures permit liquid water) are compact, and very close to the star itself.

Our observations of star systems suggest a correlation between the size of a star and the nature of its planetary system: more massive stars tend to have larger planets. As such, most planetary systems around red dwarfs are small, composed mainly of rocky terrestrial worlds (like Earth). Very few gas giants have been detected orbiting M-dwarfs. Even fewer are currently confirmed to exist.

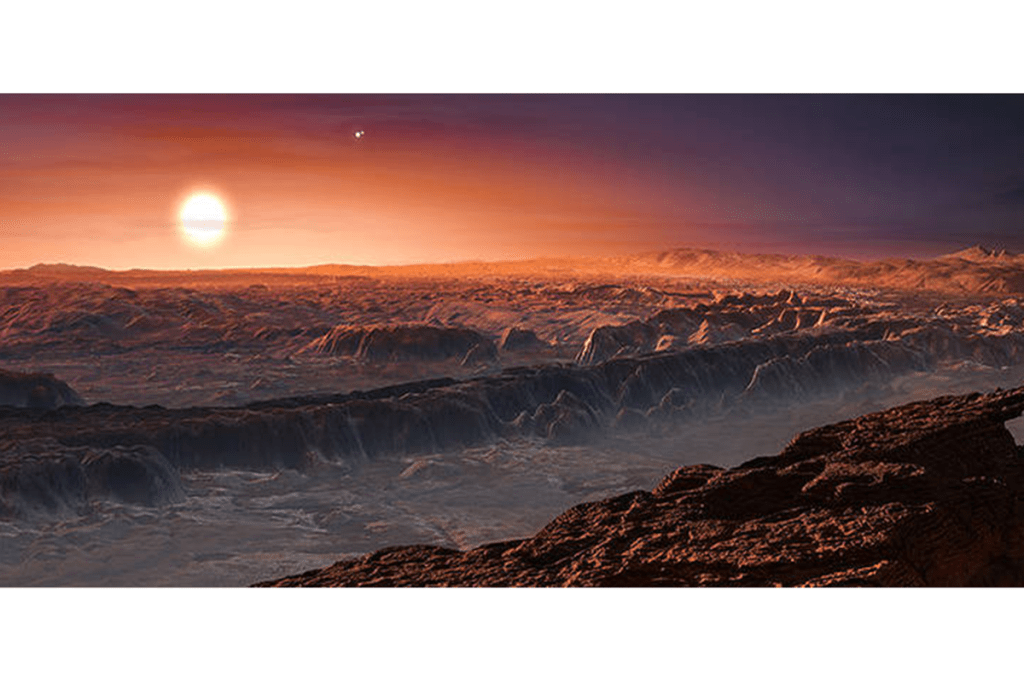

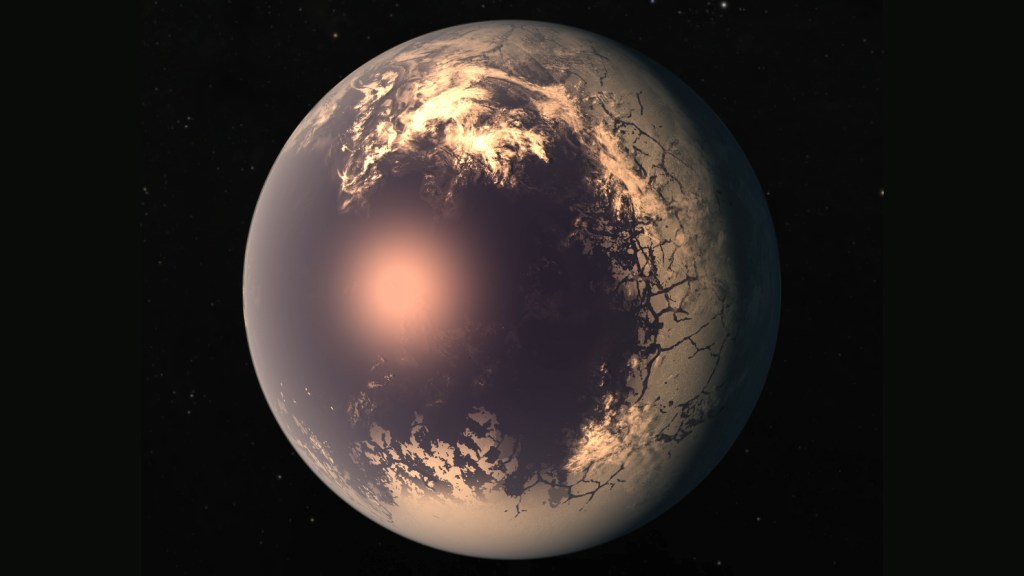

In terms of habitability, M-dwarfs have one major factor required for life to evolve: time. As they are small and cool, M-dwarfs are expected to have long lives; likely several times the expected life of our sun. For astronomers hunting for exoplanets, red dwarfs are tantalizing: they are plentiful, many are very close to us, and their dim light makes their planets much easier to see. But while that’s great for astronomy, it’s bad for habitability. As of this writing, astronomers have spotted numerous planets orbiting within the habitable zones of M-dwarf stars. But given their proximity to their suns, these worlds are likely tidally locked: they spin in time with their orbit, so one side of the planet always faces the sun. This means one side of the planet would exist in constant daylight, likely rendering it a barren desert, while the other side would receive zero solar radiation, leaving it frozen and lifeless. On such planets, it’s believed temperature variances and tidal forces would cause liquid water to pool on the sun-facing hemisphere, producing a phenomenon known as an “Eyeball Planet”. On such planets, the only habitable space would lie along a narrow band between the light and dark sides of the planet, in perpetual twilight.

That is, of course, assuming such planets would be capable of retaining water. M-dwarfs emit significant amounts of X-rays, which can break down the atmosphere of a planet. What’s worse, such stars are also extremely active, displaying intense solar flare activity. A planet orbiting close enough to lie within the habitable zone would be placed in the line of fire, subjected to coronal mass ejections that could blow its atmosphere into space.

Spectral Types F, G, and K: The Sweet Spot

Moving up the spectrum, we find what we might call “the sweet spot”: stars similar to our own. Based on our current understanding of the origins of life, it’s likely that these stars offer the best chance of finding complex life beyond our solar system: they have longer lives than larger, hotter stars, but are hot enough that their habitable zones place planets safely beyond the range of powerful X-ray emissions or extinction-level coronal mass ejections.

There are several such stars within our interstellar neighborhood. The nearest, and best candidate for finding life, is Tau Ceti, which is already confirmed to have at least one super-earth within its habitable zone (though, as you will see later, Tau Ceti may not be as ideal as it seems). Others include the aforementioned 40 Eridani, which may in fact host a planet similar to Roddenberry’s fictional Vulcan.

Spectral Types A, B, and O: Hot Giants

Some of the best-known stars in our night sky fall into this category: large, hot stars. These stars have been observed throughout human history simply because they’re easy to see. And they’re easy to see because they’re very bright, and often very, very big.

Several of our closest stellar neighbors are Type-A stars, most notably Sirius, one of the closest stars to Earth. Type-A stars emit substantially more solar radiation than our sun; thus the habitable zone would lie further out. But, there’s a key hurdle to life forming around such stars: time. Hot stars live fast and die young: most have expected life spans no longer than about one billion years. That sounds like a long time, but considering it took roughly a billion years for the earliest emergence of life on Earth, that makes it unlikely that life will ever evolve in such planetary systems. While this is bad news for the prospects of alien life, it may make planets in such stars’ habitable zones ideal for terraforming.

The X-Factors

Spectral types tell us the basics. But recent research suggests there are other factors that may determine whether or not a star’s planets could support life.

One of these is metallicity. The metallicity of a star is the measure of heavier elements (not necessarily metals) present in a star beyond the standard hydrogen and helium. Some of our most recent research suggests stars with high metallicity may have a harder time forming habitable planets, as this would affect a planet’s ability to form a protective ozone layer. Thus, metal-poor stars may be more likely to harbor habitable planets.

However, metal-poor stars are also believed to be less likely to produce gas giants, which presents another problem. Studies of our own solar system suggest that gas giants may be crucial to habitability. Their immense gravity draws in potentially dangerous impactors, forming what might be thought of as a “gravitational shield”. The Tau Ceti star system, which includes a potentially habitable planet, features a dense disk of interplanetary debris, and no confirmed gas giants. With so much debris and no large planets to deflect it, scientists believe the habitable planet might be subject to impacts similar to the one that killed the dinosaurs, as frequently as once every ten years.

One of the most exciting and frustrating aspects of writing modern hard sci-fi is that the science is always changing. We know a lot more about the nature of stars and their planetary systems now than we did ten years ago. Rest assured, we’ll know even more ten years from now. But each new discovery brings us closer to understanding the way the universe works. And each discovery brings exciting new opportunities for sci-fi writers to imagine the future. – MK