As far as star systems go, ours is fairly simple. Eight planets, one asteroid belt, and one sun. But our observations of our galaxy have shown single-star systems aren’t the rule. Many of our nearest neighbors (beyond M-dwarfs) have at least one companion star. We’ve also found numerous trinary star systems, as well as systems consisting of four, or even six stars.

On Earth, the cycle of sunrise and sunset defines our lives, dividing our existence, and that of every living thing on our planet, into days and nights. But what if we had more than one sun? Could life truly exist in a binary, or even trinary planetary system? And if so, what could such life possibly look like? This month in Science in Fiction, let’s take a look at multiple-star systems: how sci-fi has dealt with them, what science tells us, and what all of that means for the modern science fiction writer.

Multiple-Star Systems in Science Fiction

The idea of multiple-star systems has made few appearances in science fiction, but those appearances have been notable. In recent years, the very phrase “Three-Body Problem” (which, in science, refers to the model of gravitational interactions between three objects) has become synonymous with Liu Cixin’s eponymous novel. The novel has become an international sensation, as well as the first globally-recognized work of science fiction from a Chinese author. However, to even casual fans, no doubt the most recognizable instance of multiple stars in sci-fi was Tatooine. The home planet of Anakin and Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars films, Tatooine was depicted as a lifeless desert, its climate strongly implied to relate to its twin suns.

Multiple-Star Systems in Science

Our study of our galaxy has shown us that multiple-star systems are very common. In fact, one of the nearest star systems to our own, Alpha Centauri, is a trinary system. So, for simplicity’s sake, let’s start with that system, since it’s easily the best-studied.

The Alpha Centauri system is technically a trinary system, but could also be thought of as a binary-trinary system. The two primaries, Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman, are similar to our sun (Rigil Kentaurus is the same spectral class, and very slightly larger). And they orbit relatively close to one another, their elliptical orbits taking them from about 35 AU apart (about the distance from our sun to Pluto) to around 11 AU (about the distance from the sun to Saturn). However, it’s important to remember that we’re not talking about a star and a planet; we’re talking about two stars. Rigil Kentaurus may be more massive than Toliman, but both are immense bodies. For this reason, Toliman doesn’t orbit Rigil Kentaurus; rather, they orbit a common center of gravity, a barycenter, formed by their respective masses. Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman orbit their barycenter with a period of about 79 years.

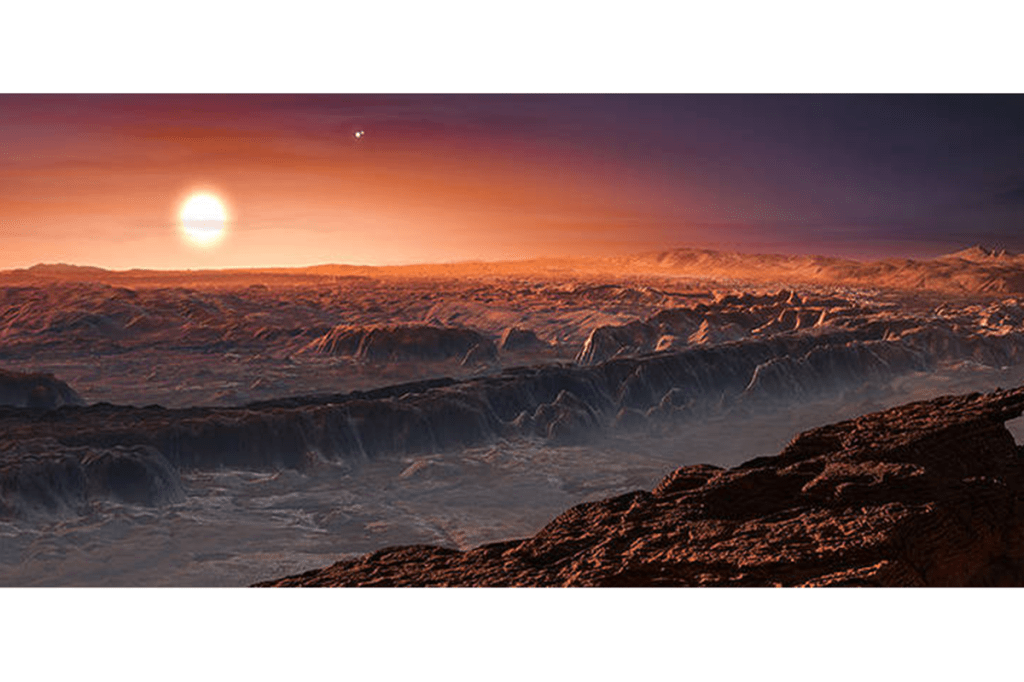

As for Proxima Centauri, you may have heard about it before. Though a tiny red dwarf, Proxima is very important to us, because

- It’s the closest star to our solar system, and

- It has at least one potentially habitable planet, Proxima Centauri b, which I’ve mentioned in previous posts.

This, of course, leads to an obvious question: if this is a system of three stars that orbit together, how can Proxima Centauri be the closest star to Earth?

For the answer, we have to look closer at the three-body problem. Proxima Centauri does co-orbit with the other stars, but its orbit is much, much wider. While Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman complete an orbit once every 79 years, Proxima Centauri orbits the same barycenter with a period of roughly five hundred years. Its orbit is not co-planar with Centauri A and B; it’s vertically-oriented. That means that Proxima Centauri moves much closer to Earth than the other two stars. And it means Proxima Centauri will continue to be the closest star to Earth for a very long time.

The mechanics of multiple-star systems is determined by a three-body problem. Such problems have many solutions, which determine the stable orbital paths of constituent stars.

So, we know what this means for stars. How would multiple stars affect their planets?

Planets in Multiple-Star Systems

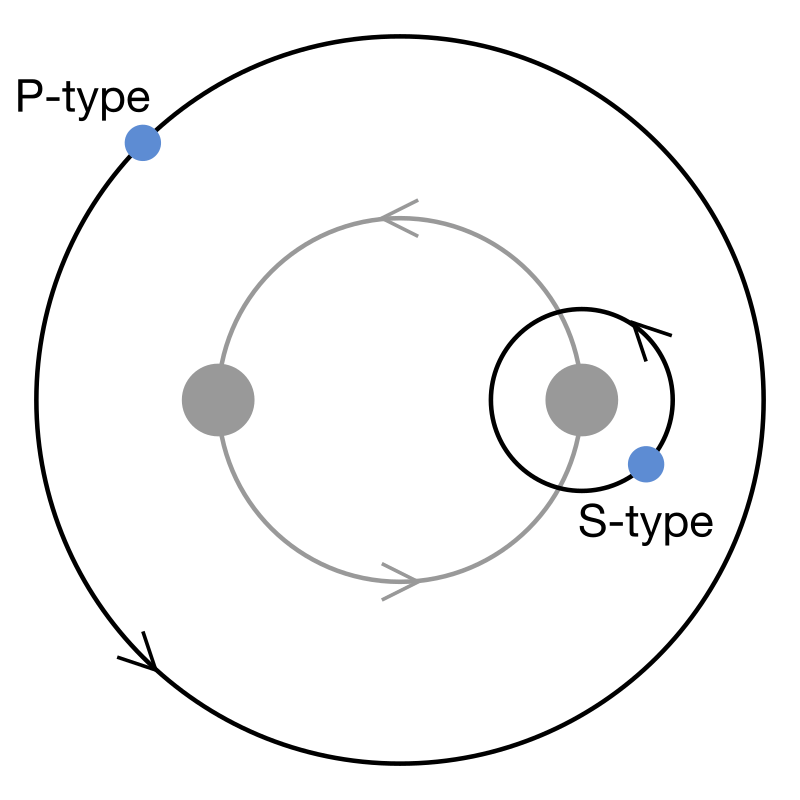

In multiple-star systems, the habitability of planets would be determined first by the manner in which a planet orbits its star or stars. When more than one star is involved, planets will adopt either an S-type or P-type orbit.

If stars are far enough apart, they may maintain their own individual planetary systems, with planets in an S-type orbit. The best example of this is right next door in the Alpha Centauri system. As mentioned, Proxima Centauri maintains its own planetary system, independent of its partner stars. Furthermore, a currently-unverified visual sighting suggests Rigil Kentaurus has at least one Neptune-sized planet in its orbit, despite its close interaction with Toliman.

In such star systems, the inhabitants of any planets would see the other component stars of their system as particularly bright stars, likely visible during the day. Depending on how closely the stars orbit one another, the other component could have a profound affect on the climate of a habitable planet. A close approach with another star would lead to extreme seasonal variances given the gradual increase in solar radiation. This could also result in disrupted day-night cycles, depending on the location of the planet with respect to the two suns.

If two stars are orbiting close to one another, however, their planets may fall into a P-type orbit, in which they jointly orbit the two stars. In such a system, the two stars would appear together in the sky, potentially blending into a continuous bar in the sky. Planets would be held at a much wider orbit. However, the aggregate solar radiation of the two stars could still allow habitable planets to form. An example of this would be any planets that may exist orbiting Rasalhague. One thing is clear, however: such star systems would have a habitable zone, and for a planet to be habitable, liquid water would need to be present. With all respect to George Lucas, based on our current understanding of science, there’s no good reason for Tatooine to be one big desert. Twin suns or not.

Life on planets around binary stars would be very different from life on Earth. The very idea of day and night could be completely different. But, if science has taught us anything, it is that life persists. It thrives at times in places where we’d least expect it. So if there are habitable planets orbiting binary or trinary stars, rest assured, life will find a way. – MK