To quote Douglas Adams, “Space is big. Really big.” Even travel between Earth and the other planets in our solar system is measured in years. The Cassini-Huygens space probe took seven years to reach Saturn. The more advanced New Horizons spacecraft took the better part of a decade to reach the Kuiper Belt, on the edge of our star system. And even it would take centuries to reach the nearest star, a paltry four light-years from Earth.

When dealing with unmanned craft, space exploration is mostly a waiting game: scientists at NASA spend years of their lives waiting for what can be mere minutes of data. But a crew complicates things: how can humans not only survive on a spacecraft for years, but also operate the spacecraft upon arrival, while potentially dealing with the ravages of old age?

One of the greatest challenges of mission planners at NASA today is figuring out how to keep astronauts safe and alive on long-duration space missions, like the planned mission to Mars. But on potential manned extrasolar missions, the problem is further complicated: how can a crew that’s been aging for decades complete their mission upon arrival? In this month’s “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a look at how sci-fi has dealt with transit times in the past, and how current science can help the modern sci-fi writer to solve what I call the “Grandfather Problem”.

Travel Time in Science Fiction

A lot of sci-fi pays lip service at best to the time spent traveling between stars or planets, for one obvious reason: it’s boring. Nobody wants to watch a movie or television show where characters spend a lot of time just going somewhere. In Star Trek, there were periodic mentions of warp travel being far from instantaneous (episodes of Deep Space Nine stated travel between Bajor and Earth took about a week at warp).

But in hard science fiction, dealing with travel times across vast distances of space is crucial. Some hard sci-fi has dealt with it by the suggestion of generation ships (for instance, the Nauvoo in The Expanse by James S.A. Corey, or the ships of the Ramans in Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke). In The Expanse, the Nauvoo was an enormous Bernal cylinder built by the Mormons to travel to Tau Ceti.

A far more common approach has been the use of cryogenics, often referred to in science fiction as “hypersleep” or “cryosleep”. It’s one of the most established tropes in science fiction, appearing in such films as Alien, Avatar, Interstellar, and the various Stargate television series. This idea involves freezing astronauts, suspending their cellular activity and (presumably) putting them into a form of hibernation, like bears. And we’ll start there, since this is the most popular trope, and it begins with one major flaw…

Hibernation in Science

The idea of putting astronauts into hibernation has become so ubiquitous that when NASA began planning missions to Mars, they commissioned a scientific study to determine how bears hibernate. The resulting research paper, titled simply “Bears Do Not Hibernate”, was easily one of the most entertaining scientific papers ever written. Essentially, a scientist entered a bear’s den during the winter in order to take its core temperature. As the researcher inserted a thermometer into the bear’s rectum, the bear raised its head to look back at them.

The research determined that bears do not, in fact, hibernate; rather, they enter a period of “reduced activity”. Subsequent research has determined that true hibernation is only seen in very small mammals, like rodents. The gist of this is that hibernation is likely impossible for humans. However, the question of cryogenics remains. So, would it be possible to simply freeze humans for long space voyages?

Cryogenics in Science

The short answer is no. The longer answer is…probably not. At least not in the way we think of it.

In science, cryogenics is defined as the behavior of materials at very low temperatures. In practical applications, cryogenics is used to preserve organic material (like vaccines) or mitigate heat (as in MRIs). The problem with freezing humans is that our bodies are composed mostly of water. Under normal circumstances, water forms crystals as it freezes. This isn’t a big problem when freezing food, but sensitive tissues, like those in the human eyes or brain, can be irreparably damaged by ice crystal formation. As of the latest research, the concept of cryogenically freezing humans while still alive, and having them wake up after being thawed, is generally accepted to be impossible.

So, hibernation and cryogenics are out. Where does that leave astronauts on long trips through space? Well, there are a few options, some of which lie along the cutting edge of modern science.

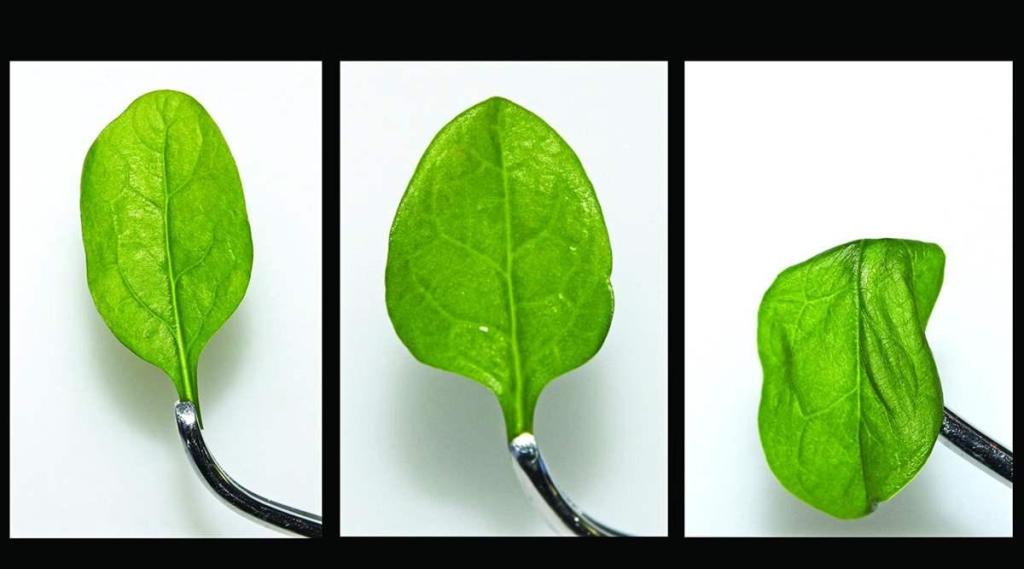

Isochoric Freezing

An emerging technology may offer hope for the freezing method. Isochoric freezing utilizes differences in pressure to lower the temperature of organic material without allowing ice crystals to form. This prevents the destruction of cells. Currently, this process is being explored for food preservation only. However, the ability to freeze something without destroying its tissues may well find human applications, if only in medicine.

Cryonics

Another alternative is fairly simple: if cryogenically freezing a human would kill them, why not simply halt their vital signs before freezing? Cryonics is the process of freezing dead humans. It’s used for preserving cadavers for study, but has seen applications in fringe circles for a very different purpose. Some, when facing a terminal health condition, elect to have their bodies frozen after death. The hope is that at some point in the future medical technology will advance to the point where not only can their condition be cured, but they can also be thawed and revived.

Recent research on mortality has suggested reviving humans long after death may be possible, provided the body was properly preserved and not permitted to decompose. Could cryonics offer a solution to the dilemma presented by cryogenics? Only time will tell.

In any event, it may be better to simply ignore the problem altogether.

Generation Ships

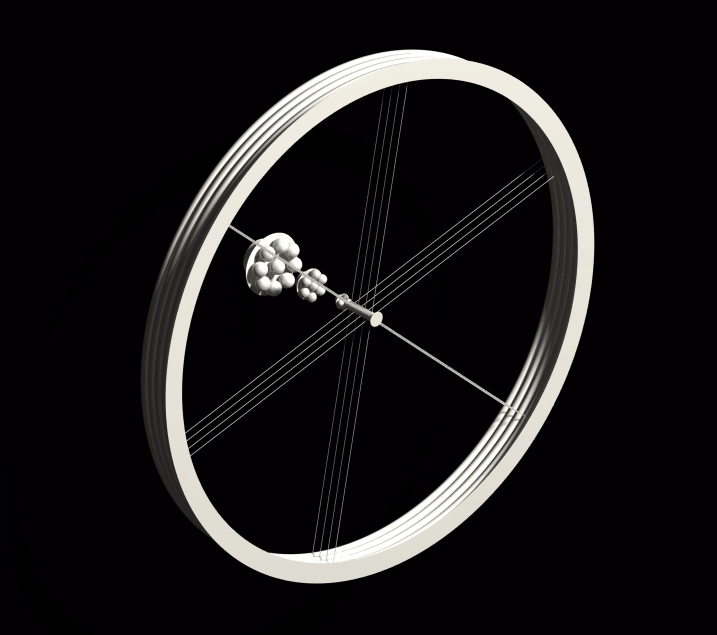

Remember the Nauvoo earlier? The idea of “Generation Ships” vastly predates its use in science fiction. Essentially, the concept involves producing a spacecraft capable of spin gravity (you may wish to refer back to one of my earlier “Science in Fiction” posts about artificial gravity, “A Fundamental Force“). The generation ship addresses the problem of human aging by accepting that the original crew of a spacecraft will grow old and die long before it reaches its destination.

In fact, the idea accepts that multiple generations of humans will live out their lives during the voyage. Aboard a generation ship, members of the ship’s large crew would be expected to have children, who would be trained to replace their predecessors. At present, this is arguably the most practical idea for long-duration space travel. But it would represent a grave sacrifice, not only on the part of the original crew, but the likely multiple generations of humans who would live their entire lives and never reach their destination.

As I’ve said before, manned interstellar travel is at best impractical without the ability to travel faster than light. Through theoretical freezing processes or generation ships, it may be possible. But it’s important to note that, even traveling several times the speed of light, the first interstellar explorers will likely take years to complete their journey. How we’ll keep them healthy and alive during the trip is one of the many problems spaceflight theorists are working out, as we prepare to take our first steps out into the galaxy. – MK

Pingback: ICYMI | Writing Tomorrow