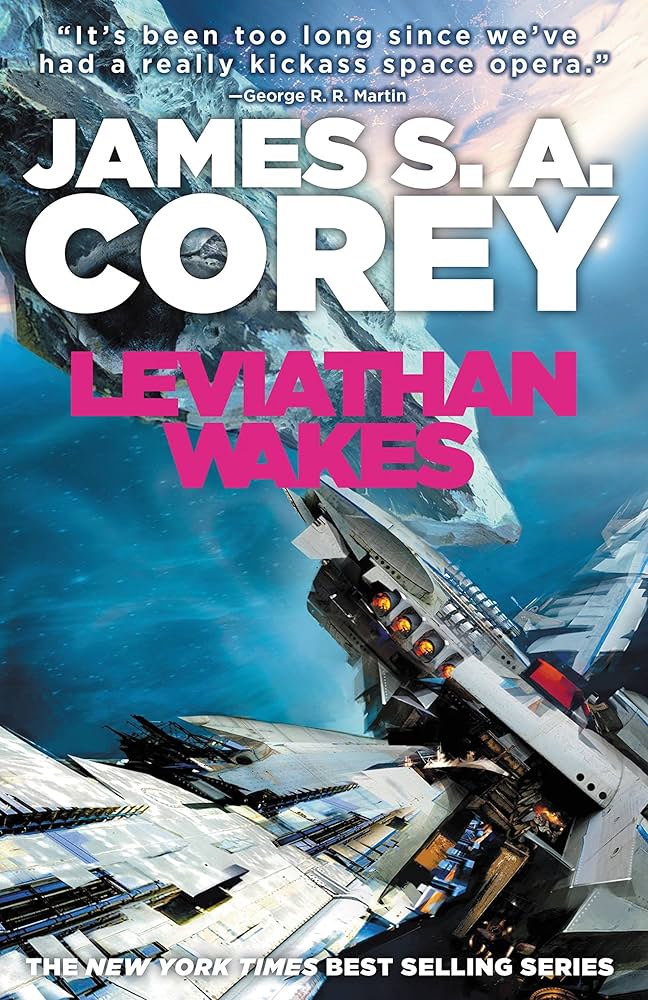

Over the past several months, I’ve been doing comps research for my upcoming novel query. It’s a hard sci-fi, multi-POV novel, which means there was an obvious starting point: the Expanse series by James S.A. Corey.

The Expanse is the towering colossus of modern science fiction. An epic drama set beneath a gripping mystery, painted over a backdrop I could only call a masterclass in modern sci-fi worldbuilding. The Expanse is awesome. It’s powerful. It’s sexy. And to a discerning sci-fi enthusiast, it’s candy. More seductive than candy. It’s heroin.

And of course the series of novels spawned the best sci-fi TV series of the 21st century so far, and arguably the best of all time. I’m ashamed to admit that, when it comes to The Expanse, I broke the cardinal rule of fiction: I watched before I read. My partner and I both loved the show, but Leviathan Wakes sat unread on my desk for several years. Luckily, comps research gave me the motivation I needed to finally dig in. Now I’m reading the fourth book in the series, having devoured the first three.

So, this week I’m making a long-overdue departure from my usual fare in “Sci-Fi Reviewed”: I’m reviewing a novel. There will be more of these posts, thanks to my comps research. But this series of posts, as with my comps research, begins with Leviathan Wakes.

The Plot

Leviathan Wakes is set in the 23rd century, in what could only be called an extreme dystopia. Mars and Earth are the new superpowers, with powerful fleets of spacecraft and nuclear weapons capable of destroying planets. The asteroid belt has been settled long enough that its residents, called Belters, have been transformed by generations in minimal gravity. Their blending of ethnicities and cultures, and their dissimilarity to the humans of Earth and Mars (whom the Belters call Inners), make it easy for Earthers and Martians to disregard them. The Belters live as virtual slaves, worked to the bone as expendable labor by all-powerful coporations.

The story of this first novel is told through the eyes of two men. James Holden is the executive officer of the Canterbury: an enormous spacecraft hauling ice between the outer planets and the Belt. Josephus “Joe” Miller is a police detective on the dwarf planet Ceres, working for the private company that provides law enforcement there.

Throughout the story, the chapters switch between Holden and Miller, as the reader gradually realizes the two are following the same plot from different angles. Everything leads to a rundown hotel on Ceres, where the two characters finally meet. After the Canterbury is destroyed in a corporate cover-up, Holden and the other survivors end up escaping a Martian warship aboard a corvette, which Holden later names the Rocinante. Miller, on the other hand, is absorbed by a seemingly mundane missing person case on Ceres, which inadvertently leads him to investigate the same coverup that destroyed the Cant. All the while, sinister forces are trying to understand the unthinkable: a product of alien intelligence, seemingly launched at Earth to corrupt and destroy all life.

My Take

Look, there’s a lot to love about Leviathan Wakes. The space mystery, a chilling first contact plot that shows how humanity’s worst impulses could shape our understanding of alien life. But the characterization of the two MCs is really what makes the story explode.

I’ve talked a lot about interiority recently, and after reading Leviathan Wakes, I feel confident in saying that these guys wrote the book on it (several, in fact). The same story is told from two very different perspectives, made even more impactful after Holden and Miller finally meet, and the two see the same things from their own unique perspectives.

Holden is abrupt and sarcastic, but he’s a deeply good person. Other characters (notably Miller) chock this up to his being from Earth, born in a place that allows black and white morality. He’s a true hero, frequently compared to Don Quixote for his tendency to get swept up in righteous causes. But though he means well, his unflappable sense of justice sees him getting in over his head frequently. And his moral compass ultimately earns the unfailing loyalty of his crew, despite his propensity for nearly getting them killed.

Miller, on the other hand, is a Belter. His life of hardship on Ceres has left him with a deep-rooted sense of nihilism, and he tends to view every situation dispassionately. His analytical nature and numbness to violence and death is befitting a career police officer…or a psychopath. And throughout the story, it’s hard to decide which of those descriptors suits him best.

For me, this book really underscored the importance of interiority, because it’s the characterizations that really differentiate it from the TV series. The book paints Miller, at least at first, as a much less likeable or pitiable character, but it does a better job of showing the process by which his obsession with his case consumes his life and destroys it. And while the show did a good job of capturing Holden’s heroism, the book frequently showed him being out of his depth, reacting rashly to situations where he didn’t have all the facts, and ultimately making things worse.

I’ve read a lot of the classics of science fiction. Leviathan Wakes was the first modern sci-fi novel I’ve read (not counting the work of Michael Crichton). And while it was a wrenching, unsettling, and ultimately deeply enjoyable read, perhaps its greatest value to me was underscoring the importance of modern literature. There’s no point in writing a novel that just shows the reader what happened. TV can do that just fine. If you’re writing a book, you need to put the reader behind the character’s eyes. That’s where books still shine. – MK