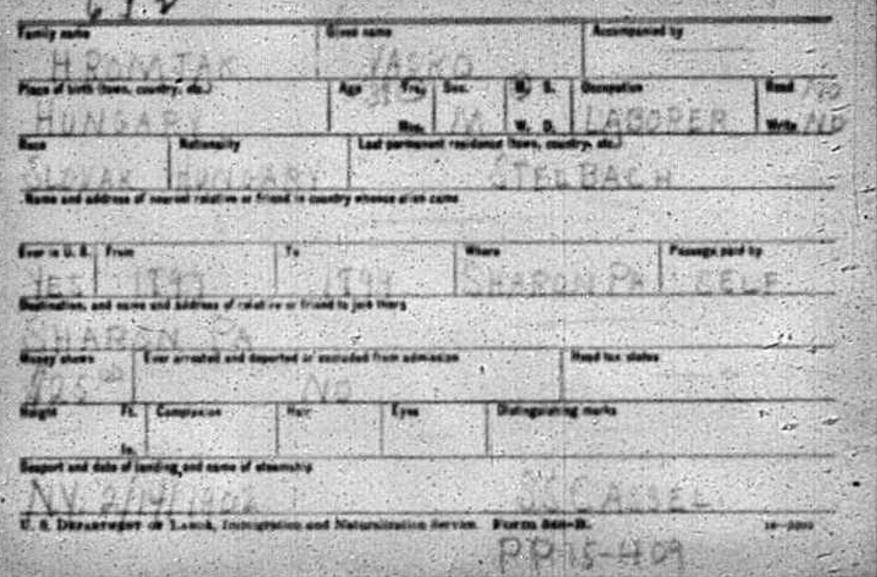

On February 14, 1902, Vasko Hromyak arrived in New York aboard the steamship Cassel. He’d made his way from his hometown in Slovakia across Europe, boarded the ship in Germany, and traveled across the Atlantic to join his wife, Susana. His ticket cost $25. That was a lot in 1902. He was a poor Slovak peasant; it was probably all he had. But he traded everything for a shot at something better. And his twenty-five bucks landed him at Ellis Island, where he became one of over twelve million immigrants to pass through the facility, and become Americans.

Being an immigrant from Eastern Europe wasn’t easy in the 1900s, or for some time after. Vasko did what he could to make money. They raised chickens in their backyard. His brother collected golf balls from the woods around the nearby golf course, and sold them at a stand. Their daughter Elizabeth delivered newspapers, stacked in her little red wagon beneath a brick. Their children had a hard time making friends; at times they’d go to visit a friend’s house only to be chased out by the parents, who screamed “Go home, hunky!“

But they persevered. They embraced the nation that shut doors in their faces and chased their children away. They learned English by reading the Sunday comics. They worked hard. And by the time their children were adults, their family’s story was about as American as any can be.

Elizabeth (“Betty”) got a job at a department store. She worked there her entire life, when she wasn’t riveting tanks during the war. She met Mike Kurpe, a child of Hungarian immigrants. She took a train to Alaska to see him after he was wounded in the Battle of Attu. Following the war, they married, and had two children of their own. Their youngest, Sue, met Tom Kuester, who was himself a child of Irish and German immigrants. Sue went to college, and became a nurse. And she and Tom had two children of their own: Michael and Christine.

Over a century after Vasko and Susana left their entire world behind, no one looks at me and doubts for a second that I’m American. And that was the dream that brought the Hromyaks to Ellis Island. On their way, they passed the statue of liberty, emblazoned with the immortal words of The New Colossus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

– Emma Lazarus

I am a product of wretched refuse. North Germans who settled in Pennsylvania. Irish fleeing famine and persecution. Poor Hungarians seeking a fresh start. Slovak peasants chasing a dream.

Today is a day of thanksgiving, and of remembrance. It’s a day on which we mark the start of the American experience. We commemorate the first wave of immigrants who arrived on these shores. Like my ancestors, they were not invited. They were unwelcome. They were fleeing persecution and injustice. All they wanted to do was live in safety and in peace, the way they chose. And after a dismal first winter, they invited the native peoples of their land to their table, in a rare show of gratitude.

Unless you are Native American, you don’t belong on these lands. We’re all strangers here. Wave after wave of immigrants have come to this nation, and faced ridicule and prejudice. Irish, Italians, and my Slavic forebears all suffered the same injustices, and they stayed anyway. And despite the cruel welcome they received from individual people, their new nation on the whole greeted them with open arms. And they repaid that by enriching it with their culture.

Our nation is exceptional in the world. When the US cricket team defeated Pakistan earlier this year, five members of the team had the last name “Patel”. We are arguably the only nation in the world whose ambassadors to other nations who can find distant relatives there. We have endured as long as we have by pulling in the wretched refuse and seeing its value. By folding the very best of every other nation into our own. We are the only nation where anyone from any other place can look at a crowd and see themselves.

This holiday is a celebration of America, and all that makes us who we are. And that means it’s also a celebration of immigration: the one, single, greatest strength of our nation. So today, in between the turkey and the pumpkin pie, take a moment to think about your own story. Your own history. And tomorrow, go out with the intent of treating those who are new arrivals in this country the way you’d have wanted your ancestors to be treated, when they passed the New Colossus.

Šťastný Deň vďakyvzdania (Happy Thanksgiving). – MK