On Earth, there are hard rules governing movement. In space, all those rules go out the window. There’s no friction, no wind resistance, no gravity. No up or down. Movement in space is perhaps the purest form of freedom one can know.

But that also poses a problem: after so long designing vehicles to move on the ground, through the water, or in the air, how do we go about moving in space? Just how, exactly, does a spacecraft move? What are the rules governing spaceflight?

Through the years, science fiction has tried to provide an answer. More often than not, the results have only underscored how deeply-ingrained our concepts of movement on Earth are. It was easier to make believable spaceflight scenes and space battles in the era before most truly understood the realities of space travel. But today, as spaceflight becomes increasingly routine, how does the modern sci-fi writer accurately depict space travel?

In this “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a closer look at how a spacecraft actually moves through space: how prior sci-fi handled spaceflight, and what we know today about what eventual interplanetary spacecraft might (or do) look like.

Spaceflight in Science Fiction

Through much of science fiction’s history, spacecraft have been designed based on the preconceptions I mentioned above. Most either resemble aircraft or ocean-going vessels, with larger (and more recognizable) spaceships like Star Trek‘s U.S.S. Enterprise or the Imperial Star Destroyers of Star Wars tending toward the latter.

This preoccupation with making spaceships actual ships has led to some head-scratching moments. In both Star Trek and Star Wars, space battles between opposing fleets of starships are almost invariably coplanar: both fleets appear with the same basic orientation and stubbornly refuse to change it, as though they’d agreed prior to the battle on which way was up and which was down.

Notably, in Star Wars starships that have been disabled are actually shown going down, as though there’s some unseen gravity well pulling at them. While in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, writers actually made the three-dimensional nature of space movement a key point of the story, perhaps the most egregious violation of the rules of spaceflight occurred in subsequent film.

During the climactic scene of Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the crew of the Enterprise steals their ship from Earth’s Spacedock, and is pursued by the newer, more advanced Excelsior. The Excelsior is understood to be much faster than Enterprise, and looks poised to overtake it, before the crew realizes former Enterprise engineer Montgomery Scott has sabotaged their engines. As a result, when attempting to go to warp, the Excelsior shuts down, and grinds to a halt in space.

While the sight of a highly-sophisticated spacecraft seeming to sputter and die like an Edsel on the side of the road makes for great cinema, it’s nonsense. Even if the Excelsior‘s engines suddenly failed, it wouldn’t slow down; rather, it would simply continue on at a constant velocity. Because moving in space follows a completely different set of rules.

More recently, however, there have been examples of sci-fi that got it right. Babylon 5, one of the gold standards in hard sci-fi television, was among the first. The Starfury fighters in the series are an excellent example of a believable spacecraft: the fighters are ringed with thrusters, and are shown utilizing full range of motion in combat. More recently, the Expanse series of novels by James S.A. Corey, and their television adaptation, gave sci-fi viewers a master class in spaceflight.

Spaceflight in Science

Movement on Earth is complex, governed by a variety of forces acting on an object at all times. Just walking around, you are subject to various forces that seek to halt your motion. Gravity attempts to press you into the ground. Friction between your feet and the ground tries to slow your stride. Wind resistance attempts to cease your forward motion (this force is less noticeable at low speeds, but comes into play when driving a car or flying in an aircraft).

But space is a vacuum, devoid of gravity. Beyond solar pressure (which, unless you’re using a solar sail, is negligible), there’s nothing to slow you down or alter your course. That means that, in space, you are subject solely to Newtonian physics. Sir Isaac Newton tells us that an object in motion will remain in motion, unless acted on by another object or force. So if you’re in a spacecraft and fire your engines, you will retain your velocity. Unless you run into something (which in space is statistically almost impossible), you’ll just keep going forever, unless you decide to stop.

There are several ways this impacts the work of a hard sci-fi writer. First and foremost, constant velocity means there’s no need to just keep firing your engines constantly. If an airplane cuts its engines, it will fall out of the sky. But a spacecraft will just keep going at whatever velocity it has attained. This is why most interplanetary probes, like the Voyager spacecraft or the Cassini probe launched to Saturn, aren’t equipped with huge rockets. Most carry only small thrusters, or simply momentum wheels. These thrusters are meant for minor course corrections only.

Voyager 2 is currently in interstellar space, having escaped our solar system on the velocity attained at launch and momentum boosts from passing through the gravity wells of the gas giants. And it will likely continue moving through space at its current velocity of fifteen kilometers per second. Forever. Now that’s fine when you’re just flinging unmanned probes into space. But a crewed spacecraft might actually want to, you know, stop, at some point. And that would require a braking burn.

In space, a vehicle’s ability to accelerate is no more or less important than its ability to decelerate. Current models for crewed interplanetary travel anticipate a flight plan that would involve two stages: an initial acceleration phase after launch to attain cruising velocity, and a deceleration phase on approach to slow down. In The Expanse, 23rd century humans used highly-efficient fusion rockets to effectively simulate gravity for the crew. Spacecraft would accelerate constantly for half of their journey, then move to “flip and burn”, decelerating the rest of the way to their destination.

That covers forward motion, but what about minor corrections? How does a spacecraft turn in space?

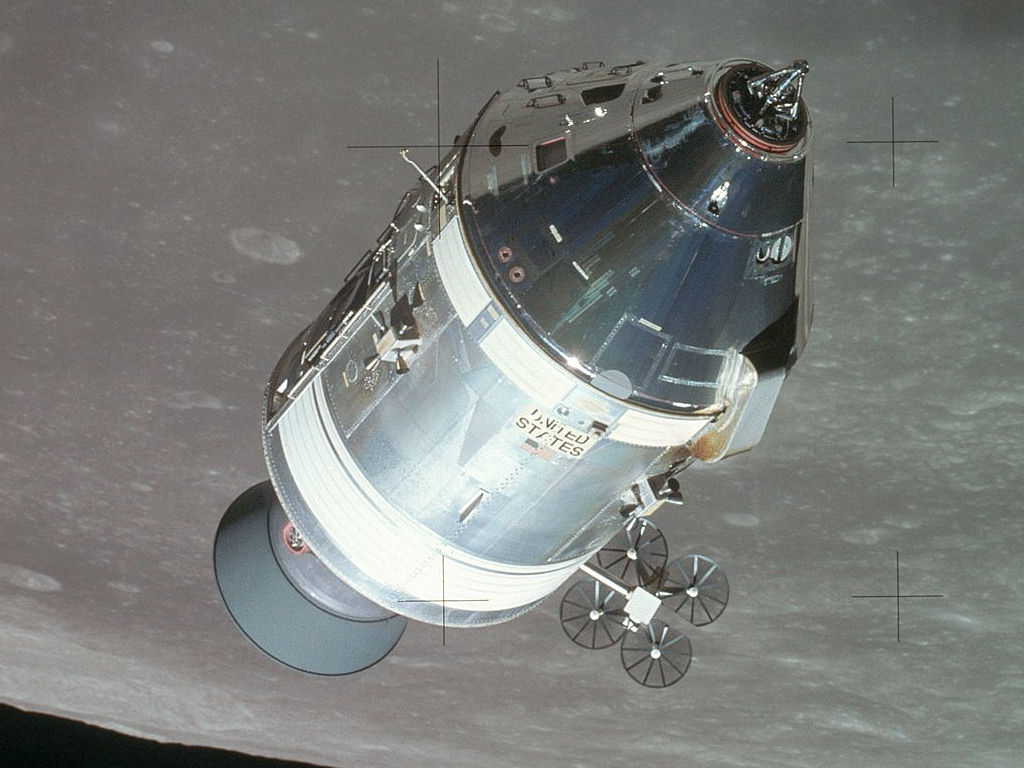

On Earth, most aircraft and naval vessels make course corrections through the use of control surfaces, which alter the path of air or water moving past the vehicle to change direction. In space, with no water or air, this is accomplished through a Reaction Control System (RCS). Typically, this takes the form of banks of thrusters, which release compressed nitrogen oxides into space. The banks of thrusters are omni-directional, because again, movement in space is perpetual. Firing thrusters in one direction will cause the spacecraft to begin rotating in the opposite direction, and it will continue to do so unless counteracted by an opposing thruster burst in the opposite direction.

This makes maneuvering in space an extremely delicate procedure. In order to change course, a spacecraft must fire thrusters to rotate, then pulse additional thrusters to fully counteract all momentum. Even a minor miscalculation can leave a spacecraft tumbling through space, as was the case with China’s ill-fated Tiangong-1 space station.

So, when we put it all together, what does the modern sci-fi writer need to know about how spacecraft move through space?

First and foremost, most spacecraft aren’t constantly firing their engines, because there’s no need. Once the proper velocity is attained, the spacecraft will continue on, and moving too fast will make it harder to decelerate upon reaching its destination. While moving, a spacecraft can rotate freely without changing its velocity. However, any changes to its attitude must be counteracted with bursts from its thrusters, or it will continue to spin.

In modern science fiction, realism is everything. Space travel will always capture the imagination, and depicting it realistically can really set your work apart from others. – MK