We all know how space travel works today. A few brave men with the Right Stuff strap themselves to the top of a towering missile, and are shot out of the atmosphere. It’s exciting. And for traveling within our tiny corner of the universe, it works great. But to get any further than our own moon, we’ll need something else.

Interplanetary travel requires us to look at spaceflight in a completely different light. First and foremost, it means a new kind of propulsion. Rocketry, at least in its conventional form, is woefully inefficient. Most launch vehicles expend the vast majority of their fuel just breaking free of Earth’s atmosphere and gravity. For humanity to become a true spacefaring species, we’ll need new technology to propel us into the greater solar system.

So, this month in “Science in Fiction”, let’s look at interplanetary propulsion: how sci-fi has done it, how science says it can be done, and how the modern sci-fi writer can make the rocket into planetary space.

Interplanetary Travel in Science Fiction

For most of us, science fiction conjures images of brave crews soaring through interstellar space, Boldly Going to distant stars. Most well-known sci-fi properties, from Star Trek to Dune, largely ignore the mundanities of what happens once the brave crews actually arrive around an alien star. Star Trek tended to play fast-and-loose with the “impulse drive” used by spacecraft at sublight speeds. Star Wars made flying through space look no different from flying in an atmosphere.

Then came The Expanse.

For most of the novel series (and subsequent television adaptation), humanity is confined to our own tiny solar system, the nearest stars well beyond our grasp. The writers better known as James S.A. Corey took the opportunity to rewrite the book (so to speak) on interplanetary travel in science fiction. And their efforts ushered in a new era of spaceflight realism in hard science fiction.

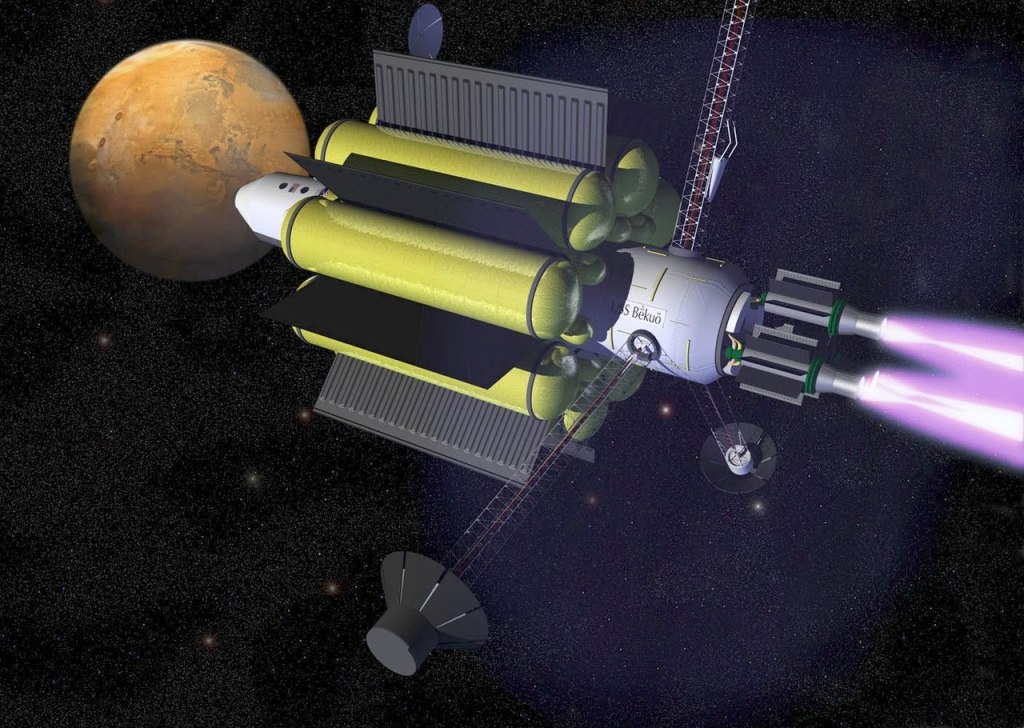

In The Expanse, most spacecraft employ an “Epstein Drive”; essentially an extremely efficient fusion rocket. And that is, in fact, one of the possible solutions to interplanetary travel. But there are many, many others, some probably closer to reality than most. So, what does modern science say about travel between planets?

Interplanetary Travel in Science

The cool thing about this topic is we actually have some experience with it. A lot, in fact. We’ve been sending unmanned spacecraft to other planets since the 1960s. Unfortunately, most of what we’ve learned doesn’t really apply to manned space travel. Because unmanned probes have a major advantage over manned missions: time.

When you’re launching a probe into space, there’s no need to rush. You don’t have to worry about the probe aging to the point where they can’t function. Or losing bone and muscle density from years in microgravity. Or being slowly cooked alive by intense cosmic radiation. Even if something goes wrong, worst case you lose a robot. Plenty more where that came from.

But sending humans into deep space carries serious risks, and that’s where our ability to rely on rocketry ends. We can simulate gravity with a centrifuge, coat a spacecraft in thick radiation shielding, but the best way to mitigate risks to spacecraft crews is to get them to their destination as quickly as possible. The most powerful rockets at our disposal would still take well over a year to get a crew to Mars, and it’s practically in our backyard. So that won’t work.

So if conventional rocketry won’t get us into planetary space, what will?

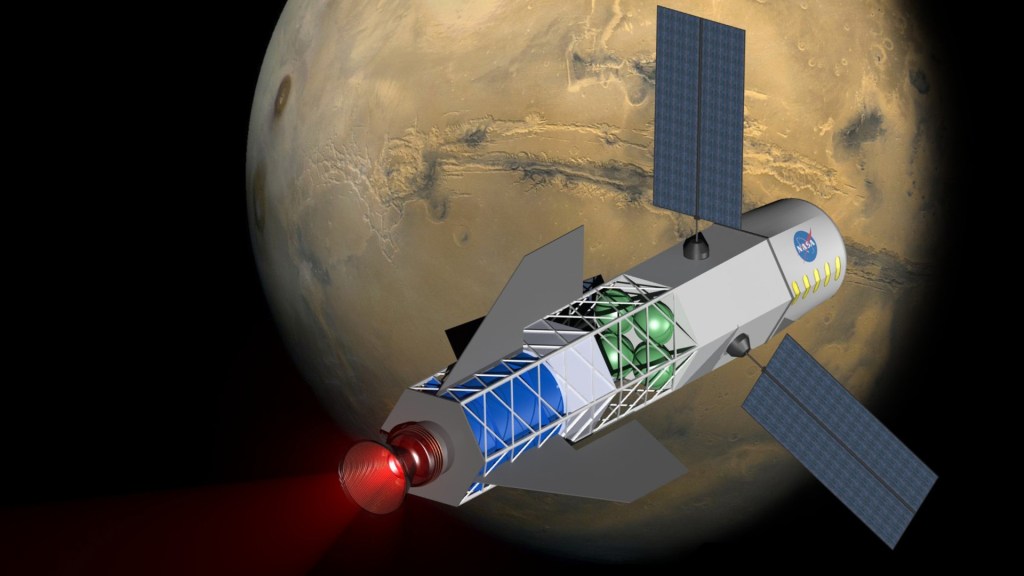

Nuclear Propulsion

The idea of using nuclear power to propel interplanetary spacecraft has been around about as long as practical nuclear power. Among the earliest concepts was Pulse Detonation: a spacecraft would use series of nuclear bombs to accelerate. Modern concepts for nuclear propulsion are a little less…wacky.

A potential nuclear propulsion system would likely take the form of a nuclear thermal rocket. Such systems would use the thermal energy from nuclear fission (rather than a chemical reaction) to heat propellant mass (typically liquid hydrogen), producing thrust.

Thermal nuclear rockets present several advantages over conventional rockets. They require less propellant mass, due in part to much higher thrust efficiency. Arguably the greatest advantage is the simple fact that it is an existing, well-researched technology. Nuclear thermal rockets have existed as far back as NASA’s NERVA project, which began in 1955.

However, even if one discounts the ionizing radiation produced by a fission reactor, there are significant drawbacks. Hydrogen is much lighter than the liquid oxygen used in conventional rockets, but it’s extremely volatile. And there’s the simple fact that a nuclear thermal rocket is still, well, a rocket.

That said, there are currently nuclear thermal rockets in development for interplanetary applications, most notably the US DRACO system, which is being explored for use as a transfer vehicle for lunar bases.

Ion Engines

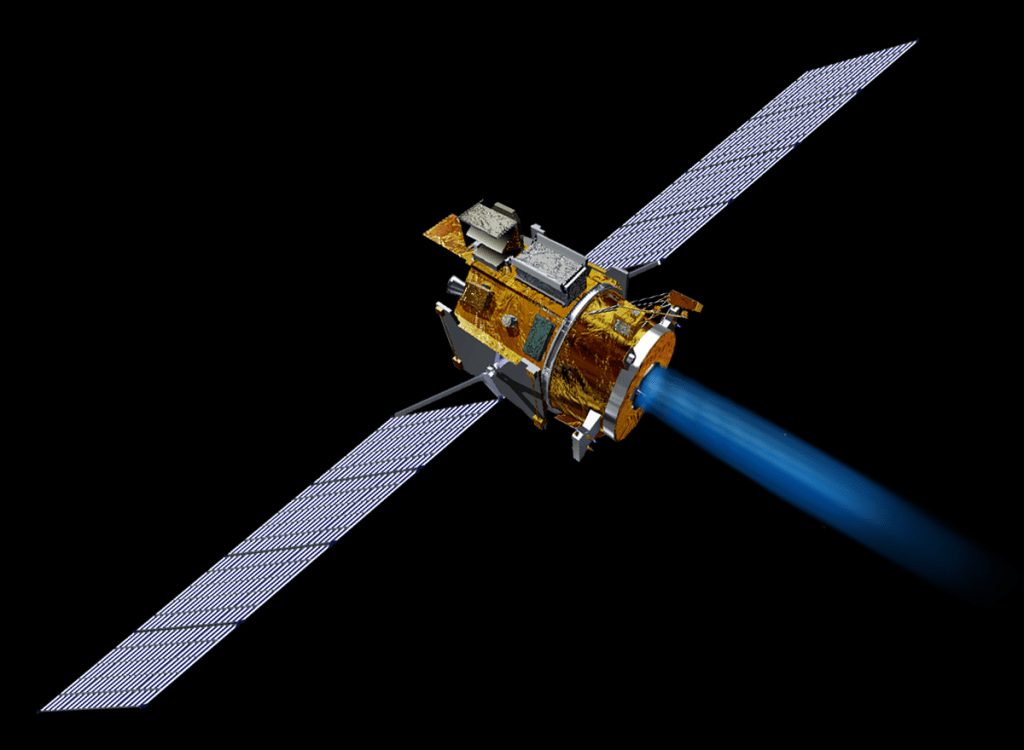

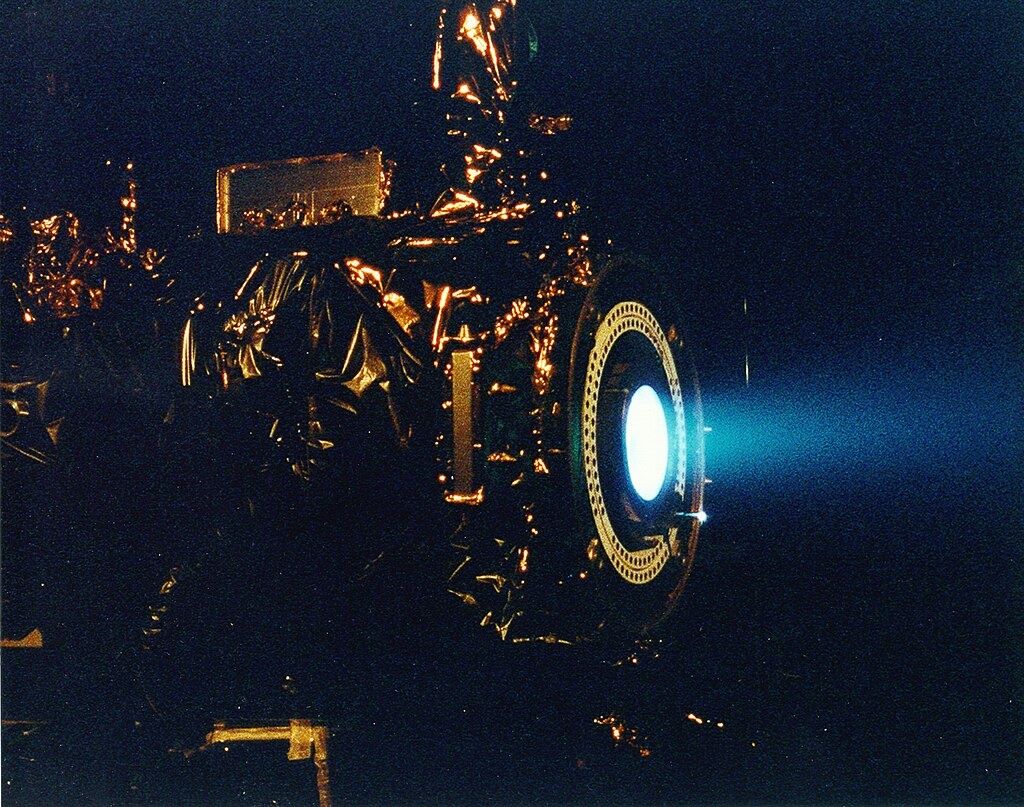

A staple of science fiction (notably with the TIE fighter in Star Wars), ion engines are a form of electric spacecraft propulsion. An ion engine produces a cloud of positive ions from a neutral gas, which is then accelerated by an electric current, producing thrust. The concept for ion propulsion vastly predates space travel itself, and practical systems have been in use since the 1970s.

At first glance, ion engines are a fantastic choice for interplanetary propulsion. The power requirements are incredibly low; NASA’s NSTAR, which propelled the Deep Space 1 probe, could operate on the energy produced by a relatively small pair of solar panels. And because it operates by ionizing neutral gas, it doesn’t require the kinds of highly flammable propellants used in conventional rocketry, like liquid oxygen, hydrogen, methane or kerosine.

The primary drawback, however, is the simplest rule of propulsion: you get what you pay for. Ion engines require very little energy or propellant, but the thrust they produce is miniscule. In most applications, ion engines overcome this drawback by operating only in space and providing constant acceleration. But to date, interplanetary applications have been limited to unmanned probes, and small ones at that. Deep Space 1, for instance, was roughly the size of a microwave oven.

It’s worth noting that NASA is currently exploring using a sort of ion engine “sled” to propel an Orion space capsule to Mars. But more than likely we’ll need a significant leap forward in thrust output to make manned interplanetary missions with ion propulsion practical.

Plasma Engines

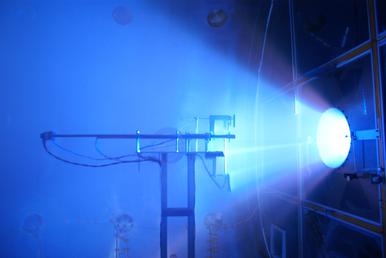

Another form of electric propulsion, plasma engines operate in a similar basic manner to ion engines. But there are a few key differences, and those lead to significantly more oomph.

For an example, we’ll use an existing design. Developed by Ad Astra, the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (VASIMR) operates by ionizing neutral gas, like an ion engine. The ion stream is then bombarded by radio waves, which excite the ions into plasma. The resultant plasma is then channeled through magnetic condensers, producing thrust.

The result is thrust that, while less powerful than a conventional rocket, is significantly greater than that of any ion engine. To give an example, the Space Launch System, currently the most powerful rocket ever produced, could get astronauts to Mars orbit in one to two years. A spacecraft launched from Earth orbit with a VASIMR engine could get there in 39 days.

That sounds incredible, but there’s a catch: once again, you get what you pay for. And the cost of all that thrust is immense power. Current designs suggest that, at minimum, a nuclear reactor would be required to power a VASIMR engine sufficiently powerful for manned spaceflight. And all that thrust also generates massive amounts of waste heat. Some designs for VASIMR-driven spacecraft incorporate football field-sized thermal radiators to keep the engines from cooking the crew alive.

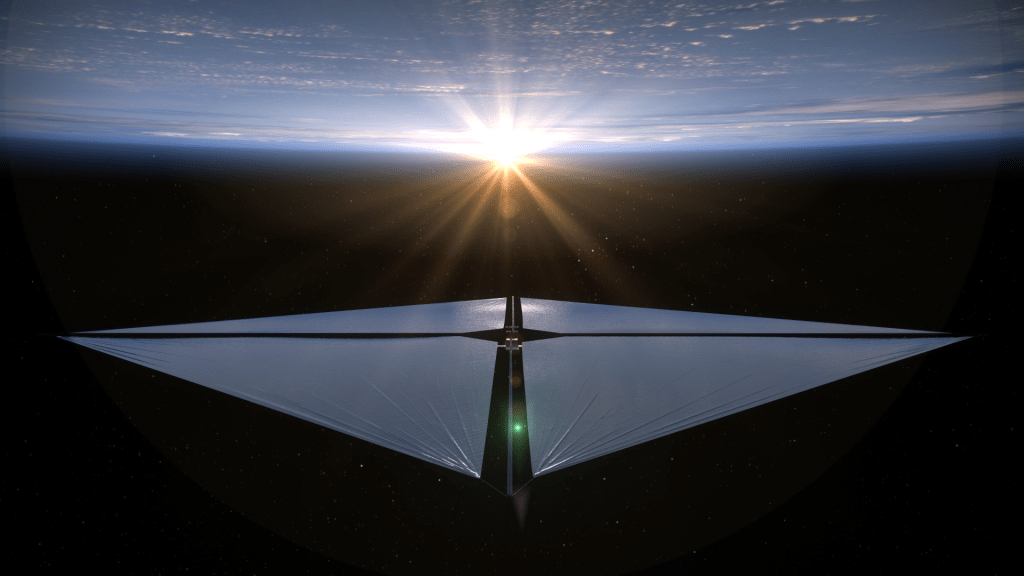

Photosails

So there are a lot of tradeoffs and drawbacks. Ionizing radiation, volatile propellants, massive power requirements. Why not eliminate fuels and engines altogether? Popularly known as solar sails, photosails use light itself for propulsion.

As we know, light is made up of discreet packets of energy, known as photons. These particles travel faster than any other known objects in the universe. We also know that light reflects off of objects (which is how our eyes are able to see; by observing reflected photons). And when light is reflected, the photons bounce off an object. That ricochet imparts momentum on the reflecting object. The first indication that photosail propulsion was possible came from minor deviations in the trajectories and orbits of early unmanned probes, which scientists correctly deduced were caused by photons altering the probes’ momentum in a vacuum.

On the face of it, photosail propulsion looks almost too good to be true: free propulsion. A photosail can provide constant acceleration with no moving parts, no propellant mass, no energy of any kind save naturally-occurring solar radiation. But while it’s not actually too good to be true, to be practical for manned spaceflight, a photosail must be three things:

1) As reflecting as possible

Your bathroom mirror might look like it’s extremely reflective, but it’s important to remember that no known substance is completely reflective. Your bathroom mirror is reflecting a lot of photons, but nowhere near every photon hitting it. And for a photosail, every little bit counts. So the sail must be extremely reflective, to an index at least on par with the kinds of mirrors used in large-diameter observatory telescopes.

2) As wide as possible

Photons are fast, but they’re also incredibly small. To generate any meaningful thrust, you need a lot of them. And beyond reflectivity, the best way to increase thrust is by increasing surface area. Studies suggest to be practical for transportation, a circular solar sail would need a diameter of at least a kilometer. For practical manned interplanetary missions, more like around ten kilometers. And making a photosail that bit would be difficult, because it must also be…

3) As thin as possible

Not only are photons tiny, but they’re massless, which means the momentum they impart is miniscule. So a solar sail would need to not only be very large but also very, very light. This low mass is accomplished by making the sail very thin. Designs for practical photosails often have a thickness measured in microns (a micron is one millionth of a meter). The thickness of such sails could be reasonably expressed in numbers of atoms.

And even all that might not be enough. With ambient solar radiation alone, even a solar sail like the one described above would generate acceleration around half a millimeter per second squared, which is all but infinitesimal. So you might still need a fourth design feature:

4) A more powerful source of light

To make solar sail travel possible in a human timeframe, you’d probably need a more intense source of photons, like a laser. In most theoretical models, this takes the form of a high-intensity laser emitter, ideally built orbiting the sun to take advantage of solar power. Essentially, these laser emitters (due to orbital mechanics, there would need to be more than one) would condense the sun’s light into a more intense, focused stream of photons, producing a sort of headwind that could be caught by photosails to accelerate more rapidly. While this would make a manned photosail spacecraft more practical, it would also at least partly negate the design’s primary advantage of free propulsion.

Fusion Rockets

Ultimately, in terms of interplanetary propulsion, the ultimate solution may be fusion power. This one’s long been a staple of science fiction; the ships on The Expanse utilize a form of high-efficiency fusion propulsion, and though they’re light on specifics, the “impulse engines” of Star Trek are understood to be a type of fusion rocket.

A fusion rocket is exactly what it sounds like: using a fusion reaction to generate thrust. Most theoretical models utilize a type of laser-inertial fusion, in which deuterium fuel pellets are injected into a bell-shaped thrust nozzle, where they’re bombarded by lasers to induce fusion. A fusion engine could also operate as a form of nuclear thermal rocket (as mentioned above), heating propellant mass to generate thrust.

As with power generation, fusion represents the holy grail of spaceflight propulsion. But it also suffers the same critical flaw: to date, we’ve been unable to reliably produce energy-positive fusion. And until we do, fusion propulsion will remain confined to the pages of science fiction.

So, which of these technologies will propel the first human explorers to the planets beyond our tiny world? For now, it’s an open question. Each of them has their ardent supporters, their advantages and drawbacks, and so far no clear answer has emerged. But it’s a question we’ll need to answer soon: manned missions to Mars could begin as early as the late 2030s. Until then, if you’re a science fiction writer, the answer is up to you. – MK