Among the planets in our solar system, there are wonders to behold. Jupiter’s massive red spot, Saturn’s spectacular rings, Uranus’s bizarre orientation, just to name a few. But even amid all this wonder, Earth is special. That’s because, among all the celestial bodies circling the Sun, only our planet is known to harbor life. Certainly complex life, life as we know it, cannot exist anywhere else in our solar system.

It can seem almost miraculous, but there’s nothing miraculous about it. Improbable, sure. But not miraculous. Rather, it could be said that our planet, and by extension our species, won the cosmic lottery. Everything lined up just right to allow our species, and all the other incredible species on our planet, to evolve. No doubt this has happened elsewhere before, and will happen elsewhere again. Improbable as our planet is, on the cosmic scale it’s a scientific impossibility that it is unique. That’s great news for writers of science fiction: after all, the truly epic sci-fi stories take place on alien planets teeming with their own life. But modern science fiction often demands realism. So, how does a science fiction writer create a believable alien planet, when to date we have not been able to glimpse such a world?

I could expound at length on the various planets sci-fi writers have dreamed up over the years. Instead, in this month’s “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a closer look at the one inhabited planet we actually know of, and focus on just what about our planet makes it so conducive to life.

Earth’s Orbit

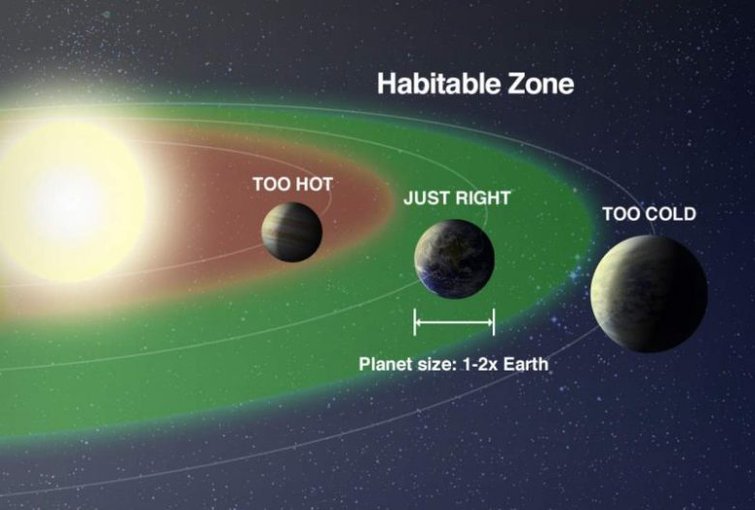

The first factor that makes complex life on Earth possible is the one most people are most familiar with: its location in the habitable zone.

Every star has what is known as a habitable zone: a region within the star system in which solar radiation is just right for liquid water to exist. Too close, and water will evaporate. Too far away, and it will freeze solid. Scientists theorize that life may be possible on planets (or moons) beyond a star’s habitable zone. Anecdotal evidence suggests there may be single-celled organisms floating in the dense clouds over Venus. There may be life forms, perhaps even cnidarians or fish, swimming in the subsurface oceans of Europa or Enceladus, warmed by the moons’ active cores. But nothing as complex as the life found on Earth could exist in such an environment.

It is important to remember that every star has a habitable zone. However, the location of the habitable zone depends on the energy output of the star. That means the habitable zone of a larger star, say Class A or O, would lie much further out than our own. And for cooler stars, like red dwarfs, the habitable zone would lie much closer to the star; potentially too close for life, placing it within the star’s awesome magnetic fields.

Earth’s Spin

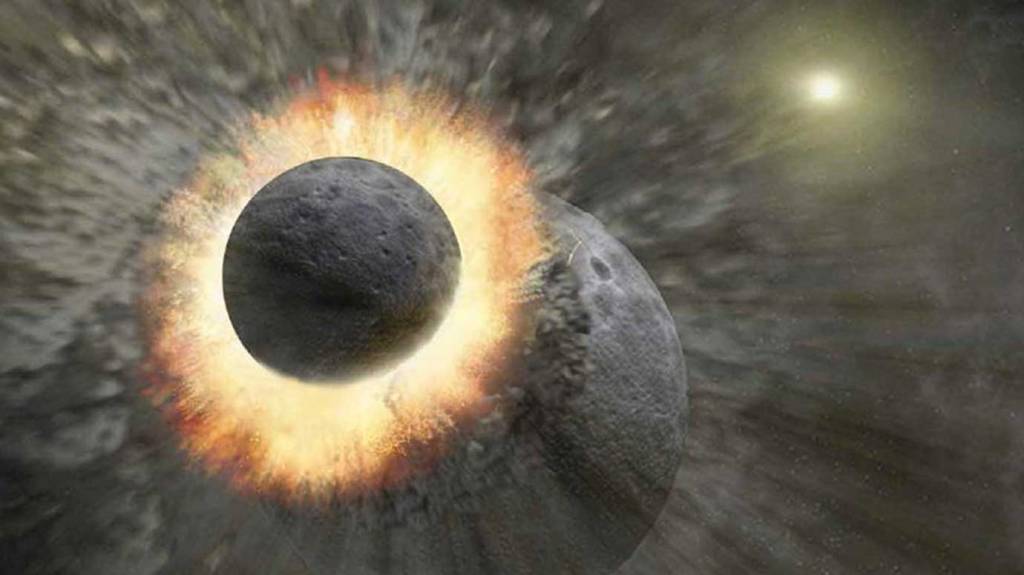

The second factor is the simple fact that our planet rotates rapidly. Believe it or not, Earth’s spin is the result of a collision: during the formative years of the solar system, our planet collided with another planetoid. It is believed this planetoid, called Thea, was roughly the size of Mars. It was a glancing blow: the collision wasn’t head-on, an event that likely would have obliterated both infant worlds. But it was enough to set the planet to spinning. It’s worth noting that Earth’s rotation is actually slowing: days get slightly longer each year.

So, what happens if a planet does not rotate as ours does? Well, a planet that does not rotate fast enough becomes tide-locked: it spins in time with its orbit. This results in a planet where one side permanently faces its star, while the other faces away. On the sun side, constant solar radiation would produce a barren desert. On the dark side, the absolute lack of solar radiation would render it cold and equally lifeless. Life on such a planet would only be possible along a narrow band running between the light and dark sides of a planet, in perpetual twilight. Whether such complex life as what we see on Earth would be possible on such a planet is anyone’s guess.

Earth’s Tilt

Not only does our planet rotate; it also wobbles. Earth’s axial tilt may not seem important, but it produces a phenomenon crucial to life on Earth: seasonal variances. Because of Earth’s tilt, solar radiation levels vary throughout the year across most of the planet. This progression forms the basis of countless diverse biospheres, maintaining our planet’s biodiversity. Life would certainly be possible on a planet that wasn’t tilted, but it would be far less diverse and interesting than what we have here. A planet with a less-pronounced tilt would likely appear from pole to pole similar to what we see along our equator.

Earth’s Companion

Let’s take a closer look at that collision.

As stated, the collision between Earth and Thea was a glancing blow. Not only was Earth not destroyed, but Thea survived as well. Mostly, anyway. In the wake of the collision, Thea fared far worse than Earth: our planet’s stronger gravity pulled material away from Thea, allowing it to grow in size. What remained was gradually re-formed, the resultant object large enough to become a sphere but too small to escape Earth’s orbit. The result was our moon.

Our moon is more important to our planet than we realize. Its miniscule gravitational pull is sufficient to produce the tides of our oceans, which contribute to biodiversity. Without it, our planet would be a very different place.

Suffice to say, there are a lot of things that make life as we know it possible on Earth. When reviewing all the myriad factors that fell into place to produce the conditions for life to evolve, it’s easy to feel that our planet must be unique. Yet, perhaps the most remarkable fact in all of this is that, in the grand scheme of the cosmos, the concept that our planet is unique in the universe is a statistical impossibility. And while all the factors covered here have contributed to the richness and diversity of life on Earth, we’re still learning just how vital each factor is to the evolution of life on the whole. Who knows what wonders might await us on distant worlds very similar to our own, or others that might look truly alien.

For more on that, watch for next week’s Science in Fiction post: Life as We Know It, in which we will explore the possibilities of life on alien planets.