It’s safe to say that one of the mainstays of modern science fiction is interstellar travel. From Star Trek to Star Wars to Dune, the truly epic sci-fi stories revolve around characters hopping across the cosmos from star to star, visiting far-flung planets orbiting alien suns.

In such stories, setting largely focuses on the planets themselves: either Earth-like worlds with biomes similar to our own, or planets truly alien by our reckoning, from the sandy wastes of Arrakis or Tatooine to the frozen tundras of Hoth and Andoria. Far too often, however, even modern science fiction tends to overlook one crucial feature: the arrangement of a star system itself.

Today, science has a lot to tell us about the likely structure of star systems beyond our own. Such considerations may be too in-depth to feature prominently in a narrative, running the risk of turning a gripping novel into a veritable atlas of alien planets. But modern science suggests that, from our own solar system to those of distant exoplanets, the arrangement of a star system can have far-reaching implications for the nature of its constituent planets. And for any life living on said worlds.

So in this installment of “Science in Fiction”, let’s answer a simple question: how would an alien star system look, and what does the arrangement of its planets mean for any potential life?

Alien Star Systems in Science Fiction

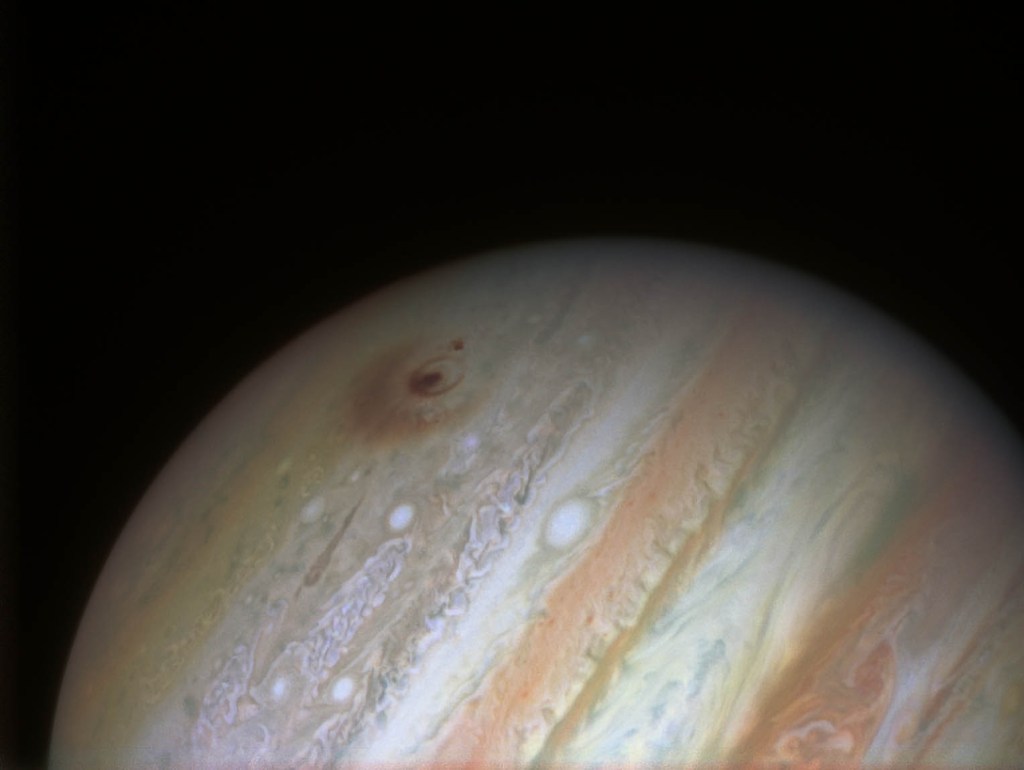

As stated above, throughout much of science fiction, there is precious little mention of the composition of alien star systems. Among the few notable examples is Pandora, featured in the 2009 James Cameron film Avatar. In the film, Pandora is depicted as an inhabited moon of a gas giant in the Alpha Centauri star system. It bears noting that, as of the latest observations, it is believed that a gas giant similar in size to Neptune orbits Rigil Kentaurus (Alpha Centauri A) at a distance of slightly over 1 AU. However, composition of gas giants is generally accepted to be determined by distance from a parent star rather than size. As such, the Neptune-like blue appearance of the planet in Avatar may be inaccurate, given the planet’s orbital distance from Rigil Kentaurus.

Exoplanets in Science

It’s hard to believe now that, as recently as 1996, the very existence of planetary systems beyond our own was purely theoretical. While many scientists accepted the existence of planets orbiting alien stars as inevitable, this was owed entirely to the idea that whatever led to our solar system’s formation couldn’t possibly have been unique. After all, to that point the mechanisms by which our own star system was formed were poorly understood. In the absence of that understanding, there remained only one way to definitively confirm the existence of planetary systems elsewhere: verified observation.

In January 1997, a group of scientists at the University of San Francisco published a paper that shook the very foundations of astronomy: by measuring minute changes in the radial velocity of the star Upsilon Andromedae, they were confident that the star harbored at least one planet in its orbit. Later observations led to a subsequent paper in 1999 indicating the existence of two additional planets.

The implications of these findings are difficult to overstate. Since 1997, astronomers across the world have compiled a growing catalogue of thousands of planets in alien star systems, now known as “exoplanets”. But perhaps the most important aspect of the discovery, both for science and sci-fi writers, was the arrangement of Upsilon Andromedae’s star system.

To say Upsilon Andromedae is very different from our own solar system is to indulge in gross understatement. Of the three confirmed planets, all three are enormous, some many times the size of Jupiter. And all orbit close to their parent star; the innermost, Upsilon Andromedae b, orbits its sun in a mere four and a half days. That means any rocky worlds – the kinds of planets capable of supporting complex life – would lie too far from their parent star for life to arise. Such planets would surely be dead, icy rocks, akin to Pluto or Sedna. What’s worse, since then we’ve learned that most star systems within close proximity to our own appear to be similarly arranged: immense gas giants close to the star, even within the habitable zone, with dead, rocky planets further out. If any exist at all.

So this is bad news for the science fiction writer. But what could this mean for the model of any fictional star system? Could it be that space, at least the space in our immediate vicinity, is practically lifeless? The answer to this question might be found far closer to home.

The Evolution of a Solar System

We’ve learned a lot about star systems over the years. But perhaps the most crucial information we’ve gleaned pertains to the evolution of our own system of planets.

Current theory tells us that when our solar system first formed, the planets were effectively inverted: the gas giants were close to the sun, while rocky bodies like our own planet sat on the outskirts. As the sun stabilized, gravity drove an incredible migration: the massive gas giants moved outward, while the smaller terrestrial bodies were pulled in. This event triggered a pivotal period in our solar system’s evolution: the passage of the gas giants through the asteroid belt hurled vast numbers of asteroids inward toward the sun in an event known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. This event showered the still-molten Earth with interplanetary debris, potentially seeding our planet with the very building blocks of life.

When this theory is applied to exoplanetary systems, the pieces of a cosmic puzzle fall into place. Of the myriad star systems we’ve examined close to our own, most orbit stars much younger, larger, and hotter than our own. Some of these stars have ages measured in millions of years; infants in the cosmic sense. Only the red dwarfs, like Proxima Centauri, are likely older than our sun. It could therefore be theorized that most star systems evolve largely the same way: gas giants develop in close proximity to their sun, with terrestrial worlds accreting further out. Over time, gravitational forces gradually move the larger planets outward, and draw terrestrial planets closer to the sun.

It is important to note, however, that the arrangement of our star system is likely far more important to life on our planet than might be readily apparent. While the migration of the gas giants was responsible for the Late Heavy Bombardment, since then their immense gravity has likely shielded the inner planets from impacts. The Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet that collided with Jupiter in 1994 was pulled off course by the gravity of the gas giant. Had Jupiter not been there, that comet could well have led to a catastrophic impact event, perhaps even striking Earth. Even with the gas giants in place, now and then an object manages to break through their protective gravitational shield. The Chicxulub impact was the result of one such miss. And we all know what happened next.

So, what does all of this mean for a science fiction writer?

The Anatomy of a Solar System

It stands to reason that most star systems, certainly any much younger than our own, would be inverted with respect to ours. Gas giants would be the inner planets, while terrestrial worlds would orbit further out. While it’s possible that some rocky planets would lie within the habitable zone (especially those orbiting larger, hotter stars), such planets could be subject to regular solar eclipses as the gas giants pass between the planet and its sun. Even if the gas giants were far enough away to avoid a major eclipse, their passage between the planet and star could lead to a notable drop in solar energy, potentially affecting the planet’s biosphere.

It’s safe to say life on such planets would be very different from what we see on Earth. Volatile climates, frequent impact events. And those can have a profound impact on evolution, as you’ll see in next month’s “Science in Fiction”. Until then, write on, and dare to dream. – MK