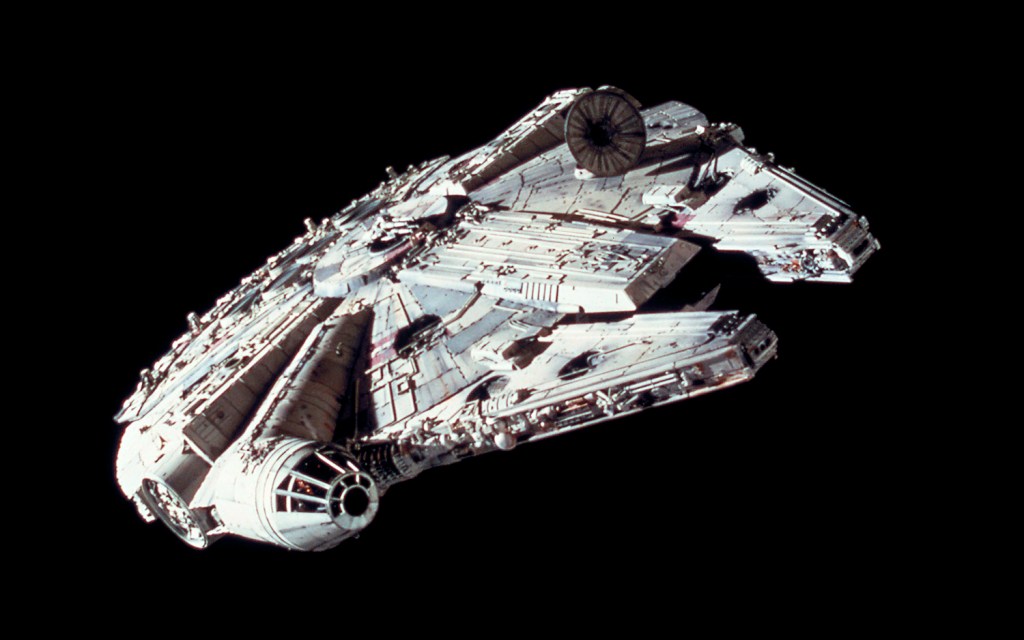

At the heart of every epic sci-fi story, there’s a ship. From the U.S.S. Enterprise of Star Trek to the Millennium Falcon of Star Wars to the Rocinante of The Expanse, science fiction often revolves around a starship that becomes home to the main characters, and serves as the primary setting. Ultimately, the ship becomes a sort of character (literally in the case of Farscape, which takes place on the living starship Moya).

But to be fair, many of science fiction’s most iconic spacecraft were designed long before spaceflight became as routine as it is now. In the 1960s and ’70s, space travel was still the realm of fiction, leaving early writers and designers free to create something meant to be more iconic than believable. But times have changed. The rising tide of scientific literacy has produced a more discerning sci-fi reader and viewer. So, how does the modern sci-fi writer deal with spacecraft design?

In this “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a look at spaceflight design: what past sci-fi got right, what it got wrong, and what today’s science tells us an eventual starship might look like.

Starships in Science Fiction

As with many of the long-standing tropes I cover in these posts, it would take an entire post just to go through all the iconic spacecraft in sci-fi history. So instead, we’ll take a look at a few of the notable ones, focusing on those who probably got it wrong, and those who probably got it right.

When looking at unrealistic spacecraft, more often than not, Star Wars takes the cake. Its spacecraft vary from those designed to resemble aircraft and those resembling naval warships. From deflector shields, to incredibly powerful engines that run on some manner of fuel never fully explained, to the way they seem to have gravity even without power, Star Wars has always played fast and loose with starship construction. And to be fair, as I mentioned earlier, when the first films were made, space travel was still in its infancy. To put things in perspective, the final Apollo moon landing occurred just five years before the release of Star Wars.

At the time, the focus of sci-fi writers (especially those working in film and television) was to create an iconic look, not make people believe these things could actually fly in space. To be fair, both Star Wars and the original Battlestar Galactica tried to make their spacecraft believable, as did the writers of Alien, one of the first true hard sci-fi films. But they were working in an era where interstellar (or even interplanetary) travel was purely theoretical.

By the 1990s, things had changed, and the television series Babylon 5 was among the first examples of sci-fi media paying attention to accepted science and spaceflight theory. While some alien races in the series are capable of producing artificial gravity, humanity is not. As such, most larger human spacecraft are equipped with spinning wheels or bars to simulate gravity. Smaller vessels are a fully microgravity environment, with the show noting that crews aboard such vessels are routinely rotated to mitigate loss of bone and muscle mass.

By the 21st century, the Expanse rewrote the book on sci-fi ship design. The writers of the series of novels (and subsequent television adaptation) took great pains to faithfully depict spacecraft, from their overall design to movement as well as life on board. In terms of interplanetary sci-fi, James S.A. Corey rewrote the book on sci-fi spaceflight design.

Starships in Science

James Cameron’s 2009 film Avatar came at a time when interplanetary travel was looked at as inevitable, and interstellar travel was a subject of serious discussion. And it showed: the Venture Star, an interstellar spacecraft seen in the film, gave a much better idea of what a starship would look like. The design includes many features that would likely appear on a real interstellar spacecraft.

So, what features are truly necessary for a starship? Let’s take a look at the basics, starting with the exterior.

Debris Shielding

Arguably the most important fact about space when designing a spacecraft is this: space is not as empty as it looks. There are diffuse clouds of particles, swarms of micrometeoroids and other incidental debris. And when building a crewed spacecraft, those can pose a serious problem.

To illustrate, let’s consider a screwdriver.

In 2023, astronauts working outside the International Space Station lost a screwdriver. It was a simple mistake. These things happen. But now, that screwdriver is orbiting the Earth. The object is being tracked by ground-based radar, which may sound like a ludicrous waste of resources. But it’s important to remember that objects in Earth’s orbit aren’t stationary, even if they appear so from Earth. These things are moving at very high speeds. Flecks of paint from aging satellites have been known to leave pits in the windscreens of space shuttles, some several centimeters deep.

When orbiting Earth, one mostly has to deal with the debris we, ourselves, have put there. That’s because Earth’s gravity is strong enough that it has cleared its orbit of incidental debris. In interplanetary space, much less interstellar space, there could be countless bits of debris, put off from the destruction of distant planets and stars.

So any spacecraft traveling beyond our solar system would need protection from this interstellar flotsam. In most designs, this takes the form of a debris shield. Such shields would likely take the form of an umbrella-like protrusion from the forward end of the craft. They’d need to be sturdy enough to handle not only debris but years of exposure to cosmic radiation. Beryllium is commonly proposed as a suitable material for debris shielding. Some designs for interstellar spacecraft feature multiple debris shields, arranged in layers, so that once one is completely destroyed, another would be there to take its place.

Fusion Power

In space, power is everything. Spacecraft require energy just to keep their crews alive. In our solar system, we typically rely on two systems to power spacecraft: solar panels and nuclear batteries, known as radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). But traversing the vast distances between stars would require immense amounts of power, as well as a level of redundancy we just don’t possess yet. Thus, for decades it’s been widely accepted that practical manned interstellar travel will be impossible without fusion power.

Nuclear fusion is the holy grail of energy. By utilizing the same process that powers the stars themselves, we would finally have the universe at our fingertips. However, contrary to what Avatar‘s writers would have you believe, powering an interstellar spacecraft wouldn’t require unobtanium (the most creatively-named substance in the history of movie McGuffin nonsense). It would require deuterium. Lots of it.

Thus, an interstellar spacecraft would likely be ringed with massive deuterium tanks, in which the deuterium itself would likely be stored as cryogenically-frozen fuel pellets. Luckily, deuterium is fairly easy to find and produce here on Earth. Unfortunately, we’re…still working out the kinks on the whole fusion thing.

Thermal Radiators

Probably the first thing anyone will know about space is that, for the most part, it’s cold. Extremely cold. The average temperature in space hovers around 2.7 Kelvin; that’s -454.81 degrees Fahrenheit. So keeping things cool in space wouldn’t seem to be a problem. But that doesn’t take spacecraft engines into account.

Any interstellar travel on the human timescale would require tremendous thrust; the kind provided by fusion rockets or powerful plasma engines. Those systems generate enormous amounts of waste heat (some designs for spacecraft propelled by the VASIMR array, a type of plasma engine, feature thermal radiators larger than the spacecraft itself). And those engines would likely be required to accelerate constantly, first to attain the proper speed and then in reverse for braking.

Thus, sufficient heat sinks are required for any manned interstellar spacecraft. We’re talking serious thermal radiators, like football field-sized. Otherwise, the spacecraft would melt down long before it reaches its destination.

So, putting it all together, we see what an actual manned interstellar spacecraft would look like. The vehicle would have to be large enough to house enormous fusion engines, carry sufficient deuterium for years (or likely decades) of constant acceleration. It would require extensive debris shielding to protect the vehicle and its crew, and would feature enormous thermal radiators. The end result would be something bearing more resemblance to the International Space Station with engines than the U.S.S. Enterprise. But in spaceflight design, aesthetics aren’t everything. The most important goal is getting the crew safely to their destination. – MK