Hello, dreamers. As we enter the home stretch of August, I am mere weeks away from entering the query trenches. And this time, I really feel ready. I have a new support structure of great fellow writers. My materials are rock solid. It’s all window-dressing from here on, but I still have more to do.

Over the coming week, I’ll be getting the last pieces of my query process in order. That includes reviewing my current list of potential agents and refining my first-round targets, as well as a “phone edit”, in which I’ll be viewing my manuscript in a different format. But overall it promises to be a welcome change of pace from the past few weeks: the weeks I spent writing a query letter.

Through listening to podcasts and the invaluable input of a new writer friend, I believe I finally cracked the code. So this week’s “Dear Sir or Madam” will be geared as much to fellow querying writers as it is to casual readers curious about the process.

The Anatomy of A Query Letter

I’ll pause while my regular readers groan, as they realize this is another post about query letters. But I assure you, dear readers, this one is different. Before, I’ve mostly written about how it’s supposed to be done and how frustrating it is.

This time, I’m writing about how I did it.

On the face of it, query letters are said to be formulaic, composed of three primary components:

-An opening paragraph containing metadata, specifically your book’s title, genre and audience, approximate word count, and comp titles

-Roughly three “plot paragraphs”, in which you introduce your plot and protagonist(s)

-A bio paragraph, providing some brief personal details and mentioning any publishing credits

All told it should be five paragraphs, coming in as close to 300 words as possible (500 is considered a hard limit, while 400 is effectively a “soft limit”).

Sounds simple enough, but the plot paragraphs in particular leave a lot open to interpretation. With the metadata and bio, realistically you’re left with at most around 250 words of real estate to describe your book. To an author who’s spent months, or even years writing an entire novel, that’s enough to make you twitch. Ask most writers inexperienced with the query process what’s important in their book, and they’ll probably say “All of it”. Because of course it’s all important. You wrote it. If it wasn’t important, it wouldn’t be in the book, right?

But as I’ve said before, the point of a query letter isn’t to explain your book; it’s to sell it. You’re trying to convince an agent to want to read your book. If you can do that in 300 words or less, heck, you’re there.

For so long I struggled with the simple task of deciding what should and shouldn’t be in my query letter. In the end, I was finally able to whittle it down, forming what I truly believe is a faithful and compelling query letter. And I did it through dissection.

First and foremost, I found the key to a great query letter is maximizing the impact of each sentence. You only get a small number of them, so you can’t waste a single one. While anyone can find the basic components of a query letter (as listed above), I realized there are what I came to call “unofficial criteria”. Essentially, your plot paragraphs must contain the following:

-Character introductions, for your main character or characters only. Other characters, even those who may be vital to the plot, shouldn’t even be named (for instance, in my query letter I refer to David Hyde, the man responsible for the entire expedition, simply as “an eccentric naturalist”).

-Setting or background information. This only really applies to genre fiction (sci-fi and fantasy in particular) which rely on worldbuilding. This can be done in a single sentence.

-Major plot points only. Your query letter should include the inciting incident and climax and tease the ending.

-The stakes. This may be the most important part of the query letter: you must tell the agent reading it what the main character/characters are trying to do and what’s at risk if they fail. A query letter should feel like a musical crescendo: you continually raise the stakes, before driving it home with the final line (I think of the closing line of the plot paragraphs as the “OR THEY’RE DOOMED” sentence).

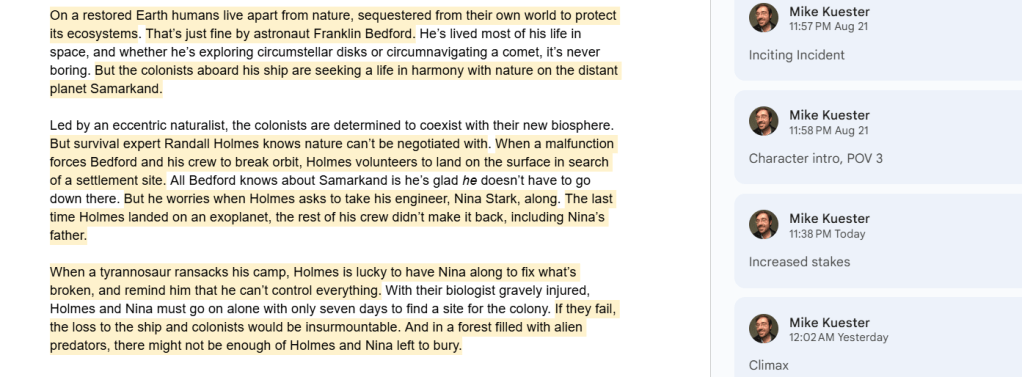

Like I said at the beginning, you only get a few sentences. And once the unofficial criteria are taken into account, the number of spare sentences drops to nearly zero. To make the most use of what I had, I began highlighting vital sentences that filled the criteria, labeling them “Character intro: POV 1”, “Establish stakes”, “inciting incident”, etc.

Now obviously it’s unrealistic to say every single sentence has to fit the criteria. Do that and you’ll end up with choppy sentences that basically read “And the this happens, and then this happens, and then…” So here and there, you have to allow yourself what I called “bridge sentences”. These sentences were where I squeezed in additional context while moving from one element to the next. But still, I tried to limit these to no more than two per paragraph (in other words, no more than six total).

What you see above is the result. Each highlighted sentence fulfills at least one specific purpose. Those not highlighted are bridge sentences, providing additional context while setting up the next element. Beyond this, I found there are a few more key points to bear in mind:

-To economize on word count, make sentences serve multiple purposes whenever possible. Fold character relationships into their introductions. Relate setting to plot. Show the plot through how it affects the characters and how they affect it. You must see how all the elements of your story influence one another.

-Though it’s not required per se, I found it easiest to proceed chronologically. When querying a multi-POV story, introduce the POV characters in rough chronological order, even if the first POV character isn’t the main protagonist. This ensures the agent won’t be confused when they move on to your sample pages.

-I cannot stress this enough, but the Characters. Are. Everything. No matter how gripping your plot may be or how clever your worldbuilding is, readers will care first and foremost about your characters. Relate everything to the characters.

Mind you, what you see above is by no means the final product I’ll be sending off to agents in a few weeks. I still hope to tighten things up even further, and between rounds of queries I plan to further refine my letter. As with your manuscript, it’s important to know when to stop, but also to recognize where things really should be improved. It took a lot longer than I’d expected to get to this point. Looking back now, it seems so simple. My hope in writing this post is that it will at least help some poor, frustrated writer save some time.

With that, I’ll say in parting “Good luck” to all my fellow querying writers. We’ve come this far; we owe it to ourselves to see this through. Always remember that the one thing that separates most successful writers from failed ones is that the successful didn’t give up. Hopefully this post will at least let you cut ahead a few steps. As for my own query letter, I’ll let you know how well it works. Stay tuned. – MK

Pingback: Writer’s Desk | Michael T. Kuester