In all of science, few things capture the imagination like black holes. They’re the ultimate unknown: an object that cannot be directly glimpsed, because even light cannot escape their gravitational pull. We’ve come a long way since their existence was first postulated: theories have been refined, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory gave us our first look at the space surrounding them. But the singularity at their center continues to evade our gaze. The only way to know what’s inside a black hole is to enter it, and if you actually survived the trip, there would still be no way to communicate your experience to the outside.

It’s no surprise that black holes have frequently found their way into science fiction. But as our understanding of these phenomena has changed, sci-fi has changed with them. So what does science have to say to the modern sci-fi writer? Let’s answer that question, in this month’s “Science in Fiction”.

Black Holes in Science Fiction

Black holes have had a lot of air time in science fiction. At present there have been three feature films that revolved (so to speak) around a black hole, starting with the 1979 live-action Disney film The Black Hole. Black holes have also gotten significant screen time in sci-fi television, including numerous episodes of the various Star Trek series.

Needless to say, through most of the earlier appearances black holes typically served as a source of dread. They were typically depicted as little more than inescapable booby traps in space. But as our understanding of black holes has evolved, so has their depiction in science fiction. Though the film Interstellar is arguably the most faithful depiction of a black hole in media, it’s worth noting that it wasn’t the first. The television series Gene Roddenberry’s Andromeda begins with the main character frozen in time due to time dilation, after being caught near the event horizon of a black hole.

Black Holes in Science

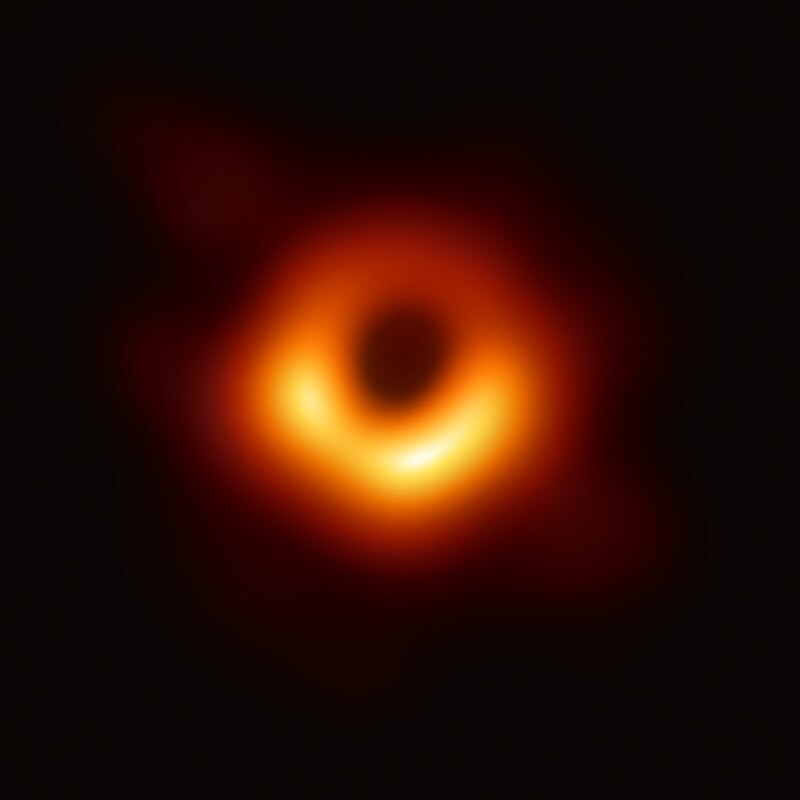

Though there’s still plenty we don’t know about black holes, we’ve learned a lot over the course of the 21st century. Our first images of them, taken in x-ray by Chandra, upended existing theories by showing jets extending from the objects; previously believed to be impossible, as nothing was supposed to be capable of escaping. The discovery led Dr. Stephen Hawking to revise his original groundbreaking theories, and his work was confirmed just a few years ago by the first direct image of the accretion disk surrounding a black hole.

It would take hours to address all the finer points of black hole theory. And as I always say, one of the cardinal rules of modern sci-fi is the reader doesn’t have to know everything (but the author does). So let’s focus on a few key points that could affect science fiction.

Black Holes Aren’t Really That Dangerous

…not unless you get close to one, anyway. And why would you do a thing like that? It is true that nothing, not even light, can escape a black hole once it’s passed the so-called “Point of No Return”. But in the cosmic sense, even the immense gravity well of a black hole doesn’t extend that far, and could be easily avoided. And black holes aren’t actually that hard to spot, because while the object itself is invisible, the material surrounding it is not.

Consider the image above. The dark spot at the middle is the actual black hole, but it’s surrounded by a dense field of matter called an accretion disk. Accretion disks are also found around forming protostars, and are composed of superheated matter. That material is subjected to intense tidal forces from the black hole’s gravity, causing it to glow. So it would be hard to just accidentally blunder into a black hole.

Black Holes “Ain’t So Black”

Until Chandra came online in 1997, the prevailing theory was that a black hole represented a singularity: a point in space-time in which the laws of physics as we know them break down. This allowed black holes to violate the laws of conservation of matter and energy. Thus it was believed that black holes sucked in matter and energy and sequestered them indefinitely. A prevailing theory at the time held that eventually the entire universe would be composed solely of black holes, leading to a so-called “Big Chill”.

But Chandra changed everything. The revelation that matter and energy were actually escaping a black hole, albeit in mangled form, invalidated existing theories, leading Dr. Stephen Hawking to famously declare “Black holes ain’t so black”. We now know that not only do black holes not hold matter and energy forever, but they also don’t last forever themselves. As they age, they gradually release their constituent mass, until eventually puffing out of existence.

Getting Close to A Black Hole Isn’t Necessarily Fatal

…though I still wouldn’t recommend it. Modern theory has dispelled the long-standing image of black holes as basically cosmic vacuum cleaners, sucking in and destroying literally anything within their reach. It’s possible to establish a stable orbit around a black hole. And even objects deeper in its gravity well will take a very long time to reach the event horizon and be obliterated.

The biggest issue would be time dilation. The immense gravity of a black hole would cause time to pass far, far more slowly for anyone nearby. The crew of a spacecraft could potentially lose years, even decades, while only seconds pass from their relativistic perspective.

It’s important to remember that we still have a lot to learn about black holes. Given their nature, they’re among the few cosmic phenomena we may never be able to fully understand. But never underestimate the human capacity to learn. It wasn’t long ago that we believed black holes would forever remain an impenetrable mystery. But until we finally discover what lies at the heart of these mysterious objects, the true nature of black holes will remain in the realm of science fiction. – MK