Power is the single biggest requirement for space travel. In an environment where humans cannot hope to survive unaided, energy is life. But we’re in luck, because our solar system boasts an ever-present, self-sustaining source of limitless energy:

The sun.

Since the early days of space travel, we’ve used the sun to power everything from robotic probes the size of toaster ovens to space stations covering an entire acre of space. Photovoltaic panels were ubiquitous in orbit of our planet long before they graced its surface. But our sun has something else to offer space travelers: propulsion.

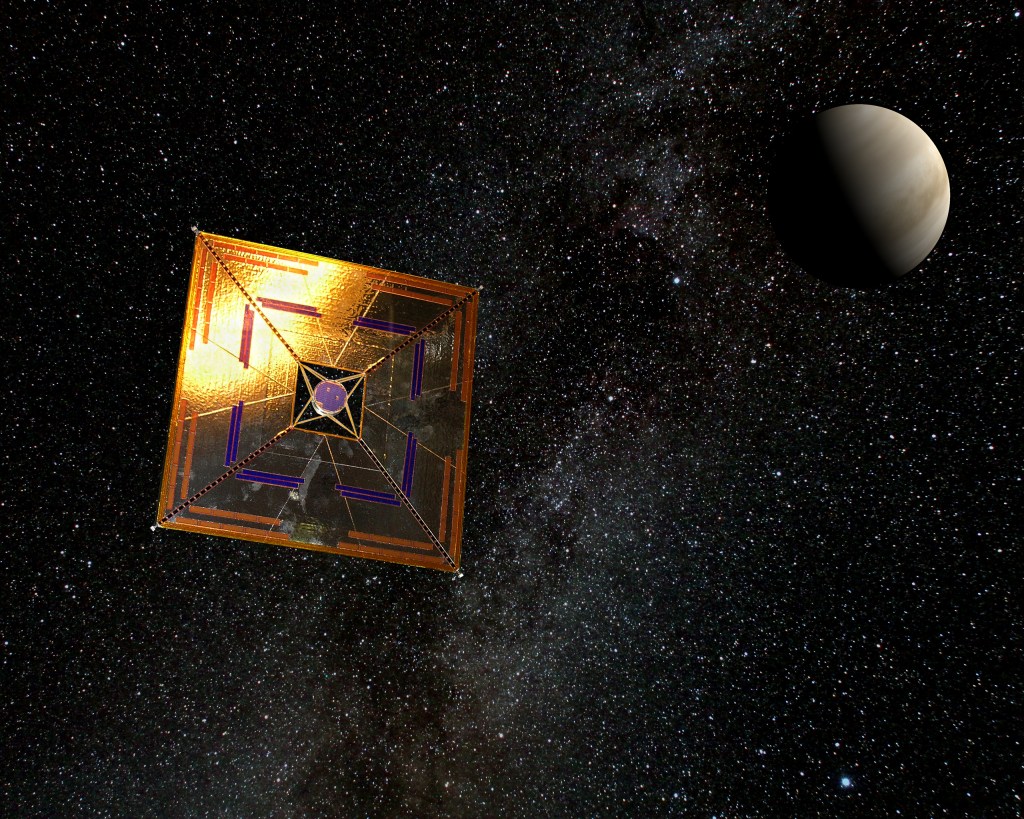

Solar sails, or more properly photosails, have the potential to revolutionize space travel, both within our solar system and beyond. So in this month’s “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a look at solar sails: how they work, what’s good and bad, and how the modern sci-fi writer can faithfully depict sailing on starlight.

Solar Sails in Science Fiction

Surprisingly, solar sails haven’t gotten much air time in science fiction over the years. And when they have, writers and designers have often paid them lip service. The villainous Count Dooku was seen using one in the Star Wars prequel films, though no attempt was made to explain how a ship like his could travel so quickly. The crew of the ill-fated U.S.S. Saratoga in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home was said to be constructing a “solar sail” to keep themselves alive, though no one explained exactly how a solar sail would generate power (writers may simply have meant to say “solar panel”).

However, roughly a decade later, Star Trek did in fact provide one of science fiction’s few notable depictions of a solar sail spacecraft. In the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode “Explorers”, Commander Benjamin Sisko constructed a solar sail spacecraft to prove the ancient Bajorans could have traveled through space thousands of years before humans.

Solar Sails (or Photosails) in Science

Although the idea of practical solar sails is fairly new, the underlying science behind them dates back to the early days of interplanetary exploration. Early on, scientists noticed minor deviations in the trajectories of deep-space robotic probes. Researchers deduced (correctly) that this was the result of photons imparting momentum as they ricocheted off the craft. That phenomenon lies at the heart of solar sail theory.

How Solar Sails Work

So we know that light is composed of discreet packets of energy, called photons. We also know that these photons travel really, really fast (the speed of light, denoted as c). And we know that these photons reflect off of atoms (it’s how our eyes allow us to see: by picking up reflected photons). When photons are reflected, it’s the result of them striking an object and bouncing off of it. That’s a collision, and as with all collisions, momentum is imparted.

It’s that change in momentum that makes solar sails work. Photons striking an object produce photopressure, which over time can alter an object’s momentum. This constitutes “free propulsion”: no energy is expended by the spacecraft to produce thrust. Constant acceleration, without the need for fuel.

That all sounds great, but this free propulsion comes with some hefty caveats. For starters, photons may travel very fast, but they’re massless. That means the momentum they impart is miniscule. So, for a solar sail to be remotely useful, it must be three things:

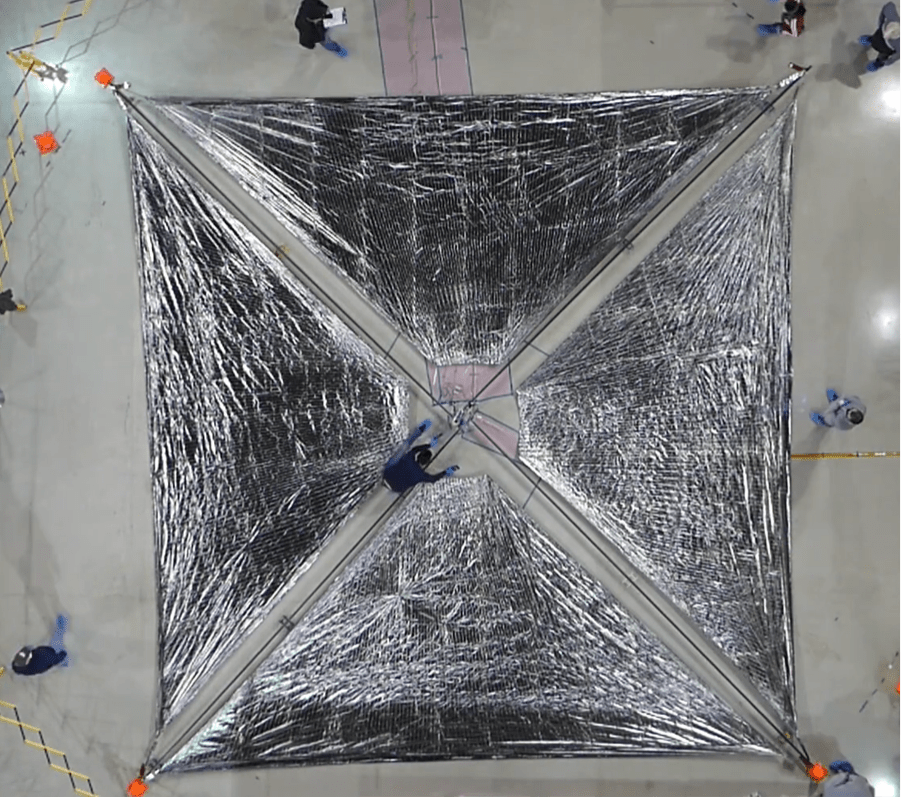

1) As reflective as possible

We’ve established that reflection of photons imparts momentum. But to make use of that momentum, you’ll need something more reflective than your bathroom mirror. Realistically, you’d need something at least as reflective as the types of mirrors used in observatory telescopes.

2) As wide as possible

Even with something extremely reflective, the momentum imparted by photons is extremely small. So you’ll need lots of them. Lots and lots and lots. To do that, you must maximize surface area. Models for a practical solar sail typically have surface areas measured in kilometers.

3) As thin as possible

Of course transfer of momentum is determined by mass. You’re already dealing with a hyperreflective object kilometers wide. You have to save on mass somehow. So you’ll have to make it extremely thin. Practical models for solar sails have thicknesses measured in microns. Such a measurement could be reasonably expressed in numbers of atoms.

Even with all of that, you’re still looking at something very, very slow. A square solar sail five kilometers wide with a thickness of 0.005 millimeters would accelerate at 0.00000163 meters per second squared. That translates to 0.14 meters per second of acceleration per day. So if you’re trying to go anywhere in a hurry, you might need one more thing:

4) A more powerful source of light

Some theoretical models for photosail propulsion include a more focused source of photons. Generally this takes the form of an array of high-power lasers, orbiting the sun to take advantage of solar energy. Even with multiple satellites, orbit would carry them out of alignment periodically. The effect would be a sort of “solar headwind”, which photosail spacecraft could use to accelerate much faster than with naturally-occurring solar pressure alone.

Despite all of that, there are already plans for solar sail spacecraft in the works. While our current technology makes navigating the solar system with photosails impractical, the technology shows more promise in interstellar applications. A solar sail spacecraft could theoretically reach Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our solar system, in as little as forty years. That may sound like a long time, but remember: nothing happens fast in space. – MK