Space stations are a staple of science fiction. From 2001: A Space Odyssey to Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, space stations have become a staple of science fiction, right up there with faster-than-light travel and aliens. The same could be said for colonies founded on alien planets. But if we can build space stations, why colonize alien planets? Why not just colonize space itself?

Among theorists, the term space colony applies specifically to a type of space station meant for permanent human habitation. The purpose of these stations would simply be to allow humans to live in space. Such objects would fall under the heading of megastructures: enormous habitats housing thousands, or even millions of people. Constructing such a space colony would require vast amounts of time and resources, not to mention some pretty incredible engineering.

But while building something like that would be…er…impractical, at our current level of technological and societal advancement, it’s scientifically sound. And ultimately, given the difficulties of terraforming dead worlds like Mars and the ugly question marks surrounding potentially habitable exoplanets, space colonies may offer our best strategy for alleviating the mounting issues of overcrowding on our tiny world.

So in this year’s final “Science in Fiction”, let’s take a closer look at space colonies: how science fiction has portrayed them, what modern science says about them, and how sci-fi writers can tackle the concept of islands in the sky.

Space Colonies in Science Fiction

Believe it or not, space colonies have gotten a lot of air time (and page time) in science fiction. The space colony is one of the prototypes of what science fiction calls the “Big Dumb Object”, or BDO. Among the most notable and earliest examples of sci-fi space colonies were the Ringworld in the eponymous novel by Larry Niven, and the ship of the Ramans in Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke.

While space colonies have long been a staple of literary sci-fi, it took modern computer graphics for them to make the jump to screens. The first notable example was the eponymous space station on the 1990s television series Babylon 5, while more recent examples include Cooper Station from Interstellar, the ring space station seen in the film Elysium, and the eponymous series of space stations from the Halo video game franchise. Some of those properties got a lot of things mostly right (Babylon 5, Interstellar), while others got things very, very wrong (looking at you, Halo).

Space Colonies in Science

While the idea of space colonies has been around for some time, practical design concepts emerged right around the time they began appearing in science fiction. When Niven and Clarke wrote their respective works, they were featuring what was, at the time, the very cutting edge of space theory. Since then, several notable concepts have been proposed.

The Stanford Torus

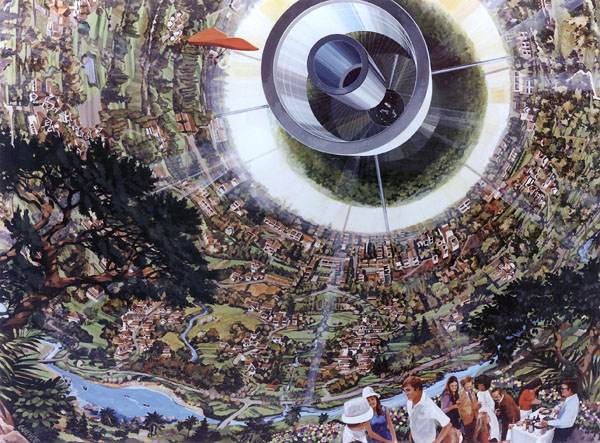

The first practical concept was the Stanford Torus. Proposed in a NASA study at Stanford University in 1975, as the name suggests the station would be toroidal (basically shaped like a donut), revolving around a central axis to simulate gravity by turning the wheel into a centrifuge. Longtime readers of this post will recognize this idea: many designs for future space stations use spinning wheels to simulate gravity, and the idea has been around since the 1920s. What set the Stanford Torus apart was its size.

Its design calls for a gravity wheel 1.8 kilometers in diameter, which would spin once per minute. The outer surface of this wheel would be filled with an artificial approximation of a glacial river valley: a central body of water rimmed with green spaces and cities, home to roughly 10,000 people. The station would be built at the L5 Lagrange point formed by Earth and its moon; the most stable point in our planet’s outer orbit, which would be necessary to maintain orbit with such a massive structure. The inner surface of the wheel would be transparent, facing massive solar focusing mirrors ringing the station’s hub. These mirrors, tinted by regolith harvested from the surface of the Moon, would provide both light and warmth within the ring, as well as nurturing sunlight for the agricultural fields that would feed the population.

Self-sustaining systems, incidentally, are critical to the construction of a space colony. The greenspaces inside the wheel would serve as life support, recycling the atmosphere, while agricultural spaces would allow residents to feed themselves.

The O’Neill Cylinder and Bernal Sphere

The Stanford Torus concept inspired two notable alternatives, both proposed by space theorist Gerard K. O’Neill. The Bernal Sphere would essentially be a fatter version of the Stanford Torus, taking the form of basically an inverted Earth. On the other hand, O’Neill’s Island One station (better known today as an O’Neill Cylinder), would be even more ambitious. It would take the form of a massive cylinder, boasting significantly more habitable surface area than the Stanford Torus. Ice caps around each end of the cylinder meant to maintain internal temperatures would also allow the colony to experience weather patterns. Imagine seeing clouds and rain inside a space station.

The McKendree Cylinder

O’Neill’s ideas were groundbreaking in his time, but by the dawn of the 21st century advances in materials science allowed NASA researchers to expand on his vision. In 2000, NASA engineer Tom McKendree proposed a new, larger version of the O’Neill cylinder. Utilizing carbon nanotubes in place of metal, the theoretical habitat could dwarf O’Neill’s original concept: nearly five thousand kilometers in length with a radius of almost five hundred. Even with transparent panels meant to allow sunlight into the cylinder, the resultant space station would boast a habitable surface area the size of Russia.

For the inhabitants of something so large, life on the inner surface wouldn’t be too different from life on Earth. They would likely live in large cities, interspersed with vast green spaces and potentially diverse ecosystems. Such a station would experience weather patterns similar to those on our planet, expect the weather could be carefully controlled.

One of the most exciting aspects of modern science fiction is imagining what everyday life would look like for future humans living in space. Inhabitants of space colonies could live out their entire lives, from birth to death, held by spin gravity to the skin of an inverted world. To us, the idea of looking up into the sky and seeing the tops of trees and skyscrapers might seem totally alien. But for someone born in an orbital habitat, life stuck to the outside of a sphere might seem every bit as strange. And that is a lot of fun to think about. – MK