On October 15, 1997, a Titan IV rocket lit the early morning sky over Cape Canaveral. It was a towering rocket, built to carry a massive payload. Once in orbit, it released that payload: a 22-foot long, 5,500 lb. unmanned interplanetary spacecraft. It was the second-largest unmanned space vehicle ever constructed (eclipsed only by the Soviet Phobos 1 and Phobos 2 probes, launched to the moons of Mars). Powered by nuclear batteries, the spacecraft was considered the last of the “Big Space” missions. As it was designed to explore Saturn, it was only fitting that the probe was named for two astronomers who were instrumental in the planet’s early study: Giovanni Cassini and Christiaan Huygens.

The launch of Cassini-Huygens was big news in the science community. In an era not far removed from the triumphant Voyager missions, major space projects captured the public’s imagination. Yet even amid a flurry of activity in space exploration, with the construction of the International Space Station commencing and only months after the Pathfinder lander touched down on Mars, Cassini was special, if only due to its intended target: Saturn. With its complex rings and diverse moons, few other celestial bodies within our solar system have proven so captivating. While man had been eyeing Saturn for centuries, by the time of Cassini‘s launch, it had been less than twenty years since the Pioneer 11 spacecraft became the first probe to view the planet up close. The subsequent Voyager missions a year later answered many questions, but left us with many more.

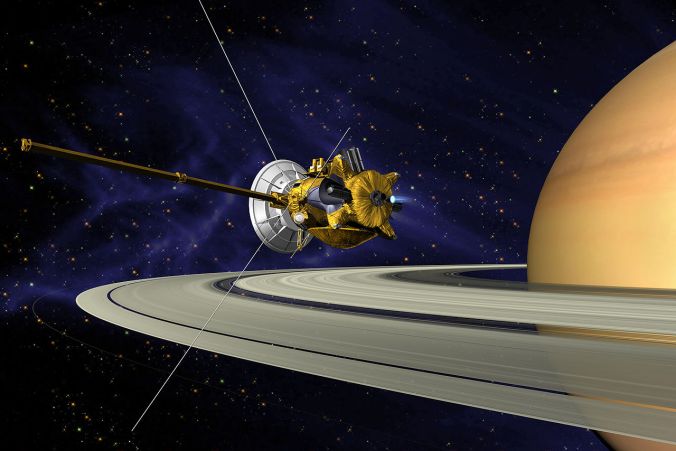

Artist’s rendition of Cassini entering orbit of Saturn, released by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 2002

And so, the launch of Cassini in 1997 was met with well-deserved fanfare. Major science publications touted the spacecraft’s complex technology, filling their pages with eye-catching artist renditions of the probe in its eventual orbit of Saturn. Then came the early morning launch, and then the waiting began. Upon reaching orbit, Cassini took off on a series of gravity-assist maneuvers, intended to build speed for its long, lonely voyage. At that point, most of the general public tuned out. The images of Cassini orbiting Saturn, and indeed the awareness of Cassini itself, faded from the public zeitgeist. After all, the probe would not reach its destination for nearly ten years, and for most, the idea of a probe careening through empty space isn’t something that captures the imagination.

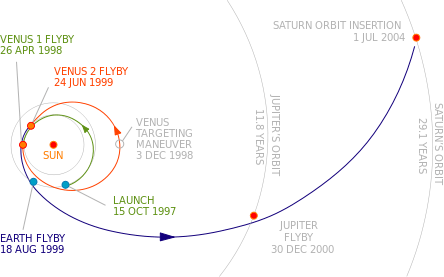

Diagram of Cassini‘s trajectory, from NASA JPL

For years, Americans at large paid little attention to the massive probe speeding off toward the outer planets. Its flybys of Venus were fairly uneventful. It’s image of Earth’s moon was hardly noteworthy. And after leaving Earth for the last time, Cassini offered little beyond a brief flyby of Jupiter and a distant, grainy image of the asteroid 2685 Masursky.

While Cassini‘s images of Jupiter were noteworthy, few paid much attention to the distant probe until 2004, when it returned its first high-resolution images of Saturn. Then, everything changed, as the real mission began…

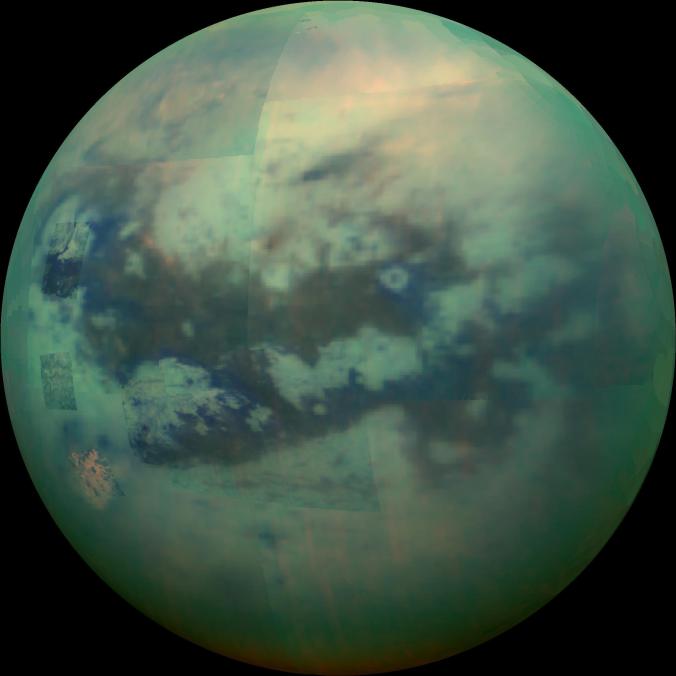

From there, the rest is history. Cassini lived up to the hype. It accurately measured the rotational period of Saturn by monitoring radio emissions. It took detailed measurements of the planet’s iconic rings, noting minor disturbances in the structure that had gone unnoticed as the Voyager probes had sped by. It peered through the methane clouds of Titan and mapped its surface, took meteorological data. It discovered evidence of an ocean of liquid water hidden beneath the ice on Enceladus. On Christmas Day in 2004, Cassini released the ESA Huygens probe, which landed on the surface of Titan, becoming the first man-made object to land on a body in the outer solar system. From its landing point, Huygens beamed back images of icy rocks, strewn across seas of liquid methane.

Image of the surface of Titan, taken by the Huygens probe

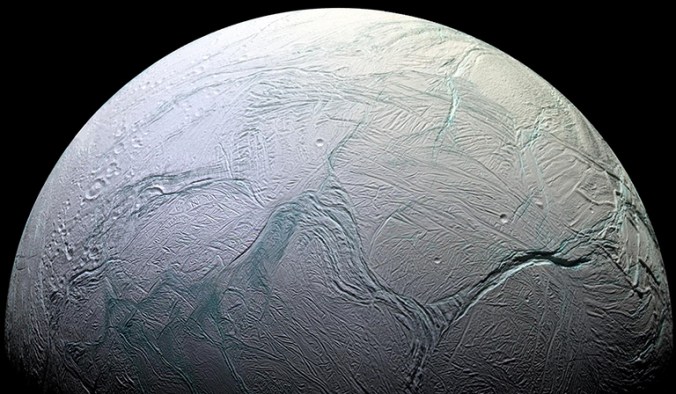

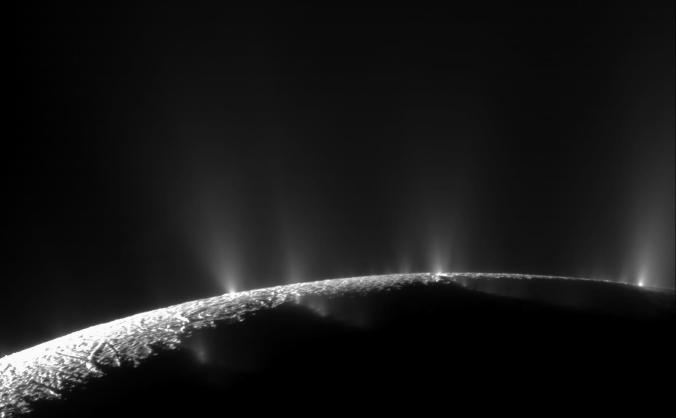

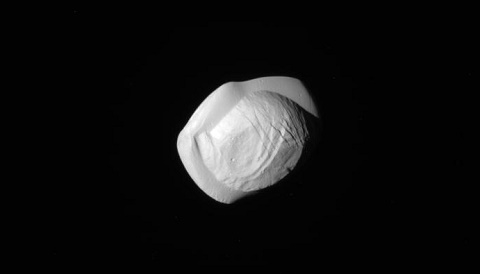

Cassini couldn’t be stopped. Its mission was extended twice, ultimately stretching into late 2017, as the discoveries kept coming. Cassini observed a hurricane at Saturn’s south pole, the first such storm structure observed outside of Earth’s atmosphere. It glimpsed plumes of water ice spouting from the surface of Enceladus, seeding Saturn’s rings. It made close flybys of numerous moons, and discovered seven additional moons, bringing Saturn’s total to a staggering 62.

Through it all, Cassini wowed the people of Earth with breathtaking images. Its high-resolution cameras allowed us to see the second-largest planet of our solar system as never before, in stunning detail.

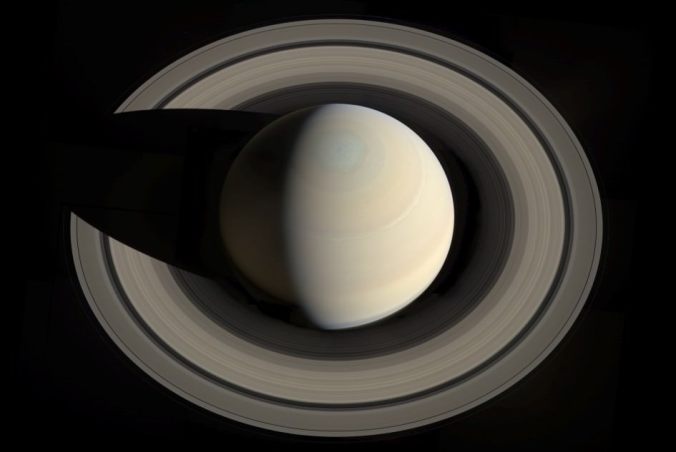

Image of Saturn’s southern pole, taken by Cassini in 2013

Detailed image of Saturn’s rings, taken by Cassini

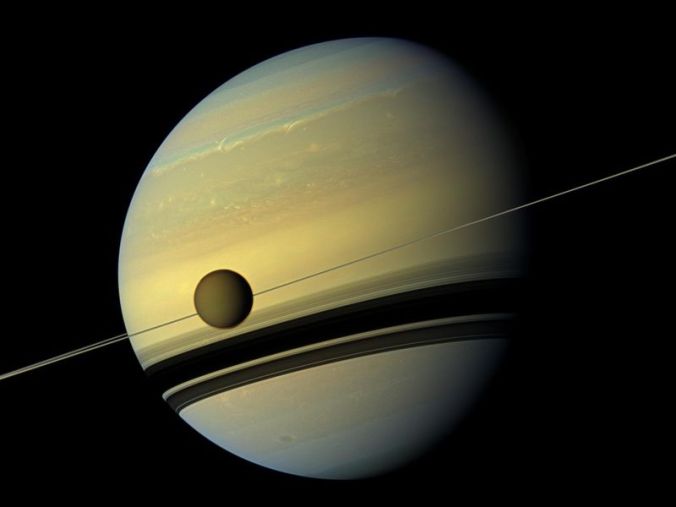

Image from Cassini showing transit of Titan over Saturn

Image of Titan’s surface, taken by Cassini

Image of the surface of Enceladus, showing ripples in the ice likely caused by a subsurface ocean

Plumes of water ice erupting from cryovolcanoes on Enceladus. The plumes feed into Saturn’s E-ring

Iconic image of Pan, Saturn’s “Ravioli Moon”, taken by Cassini

After seven years plying its lonely course through the solar system, Cassini found its moment of fame. For thirteen years, we gazed through its lenses upon natural wonders that defy imagination. Through Cassini‘s sensors and cameras, we came to a far greater understanding of one of the most incredible features of our star system, seeing Saturn as we could never have dreamed.

Then, it was over. After over a decade of exploration and wonder, the Cassini mission drew to a close. Cassini was set on a death spiral, falling into Saturn’s immense gravity, capturing further remarkable images even as its time grew short. Then, at last, Cassini fell out of contact. On September 15, 2017, Cassini sent its final transmission to Earth. Moments later, the spacecraft was vaporized by Saturn’s atmosphere, its constituent atoms melding with the planet that had been its constant companion for so many years. Saturn and Cassini were bonded forever.

Now the breathtaking images have stopped coming. The news, and the American people, move on. Yet for many, this is a bitter day. Between development, launch, transit, and finally its 13 year mission, for many NASA researchers Cassini‘s demise marks the end of nearly thirty years of hard work. For those dedicated men and women, Cassini‘s journey was uninterrupted. They were there, waiting and hoping, as it accelerated past Venus in 1998, as it flew by Earth in 1999. They sat patiently as the probe made its long voyage to Saturn, and reveled in discovery over its decade of exploration. It’s little wonder that there were tears from many of the researchers. For them, today marked the conclusion of a lifetime of hard work.

Planetary science, as with all branches of astronomy, is a study in patience. Researchers at NASA spend years of their lives working tirelessly on projects that will not come to fruition for years further. Sometimes, as was the case with earlier probes, all of those years of waiting may yield but fleeting moments of discovery. Then, it’s over. The computers are turned off, logs archived, images relegated to computer backgrounds and museum gift shops.

And yet, they keep going. They remain patient, they keep waiting. As Carl Sagan once put it, “It is said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience.” There may be no greater expression of this than the act of working tirelessly for over a decade, to be rewarded in the end with images that, by their very nature, make one feel very, very small. It may be that the greatest lesson of the Cassini mission, especially for our society today, lies in its purpose. Cassini was never designed to yield tangible results, at least not in the economic sense. The probe wasn’t assessing potential for colonization of Saturn’s moons, nor was it sizing Saturn or its moons up for mining. It wasn’t scanning for profitable raw materials, and while its famous images might have sold a few calendars, that wasn’t the point.

Cassini was about accomplishing something more abstract: it was about satisfying our curiosity. Over the course of its mission, it greatly expanded our knowledge not only of Saturn, but also of its system of moons, the possibility of life elsewhere, the history of our solar system, and indeed the nature of the Universe itself. The Cassini spacecraft was a massive, highly-sophisticated, extremely expensive probe designed for no purpose beyond scientific discovery. It was a monument to the defining trait that lies at the heart of our human nature: the burning need to understand how the universe works. To explore further. To push boundaries. To answer questions. To know.

Despite all our perceived victories here on Earth, missions like Cassini tower over all other accomplishments. They stand as the greatest triumphs of the human spirit, and resounding proofs of what we can accomplish when we place the pursuit of knowledge above all else. The unqualified success of the Cassini mission should serve as encouragement, reminding us that in the end, the quest for understanding, the pursuit of science, yields rewards that defy price tags, and transcend earthly concerns.

Rest assured, there will be further missions of exploration. Only a year after Cassini left Earth, NASA launched Deep Space 1: a demonstration spacecraft. It was much smaller than Cassini, barely the size of a microwave oven, yet far faster, driven by a prototype ion engine. During Cassini‘s time in orbit of Saturn, New Horizons arrived at Pluto, completing the family photo of our solar system, and the Juno spacecraft arrived in orbit of Jupiter, ready to give our star system’s largest planet what might be considered “the Cassini treatment”. Our journey through the stars continues.

How long it will continue, however, is up to us. There will always be those who oppose space exploration for its own merit. Those who insist that spending money on something that yields no clear economic benefit is foolhardy, or that problems here on Earth should always take precedent. Those who understand the value of space exploration, those who believe that the stars are our destiny, must continue to keep the faith. Right now, NASA lies at a crossroads. Current plans to send a lander to Europa, to send humans to Mars, and other pursuits, are in jeopardy as the same tired arguments have surfaced once again.

It’s up to us to remind those in power that, while it is important to address our concerns here on our own planet, by investing in space exploration we are securing our future. We were never meant to remain on Earth, and if we venture out into the stars without first understanding the universe around us, we will no doubt find ourselves woefully unprepared. It is in our nature to explore, to question. And indeed, it says a lot that our species was willing to invest vast amounts of resources to send a massive, nuclear-powered spacecraft out into the outer solar system, just to satisfy our curiosity. That curiosity is our greatest asset, and one we need now more than ever.

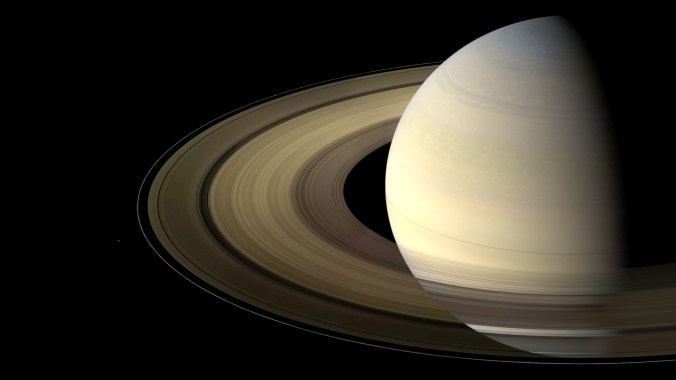

Image of Saturn and its rings, taken by Cassini

Hi Mike

This article is excellent!! We enjoyed reading it very much!

Mom and dad

LikeLike