In our solar system, there exists an object of immense power. It generates a staggering 390,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 Watts of energy per second. Its energy is crucial to our star system. Without it, the mighty gas giants beyond the asteroid belt would freeze solid. And it manages to not only warm the farthest reaches of the system, but also to keep every living thing on our planet warm and alive.

Imagine what we could do with such power.

Nuclear fusion has long been considered the holy grail of energy production. A workable fusion reactor could be self-contained, self-sustaining, and provide near-limitless amounts of power. Thus far, unfortunately, practical application of fusion power has remained in the realm of science fiction. But great leaps have been made in recent years, and we may finally be on the verge of a fusion-powered world.

So, what does fusion power mean to the science fiction writer?

Fusion in Sci-fi

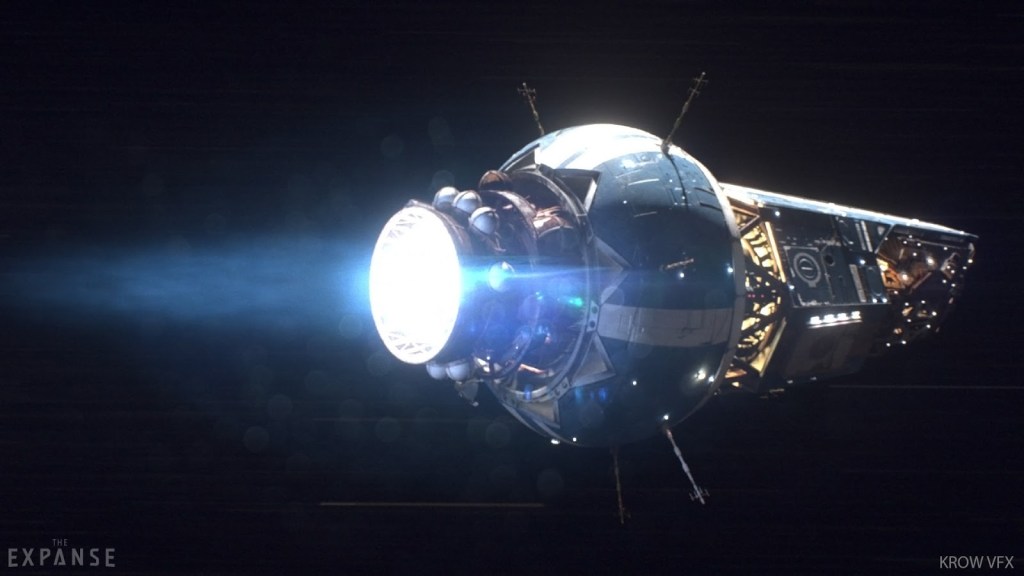

Fusion power has been a staple of science fiction for decades. From Star Trek to The Expanse, fusion energy has frequently served as the power source for fictional spacecraft, and for good reason. To quote Douglas Adams, space is big. Really big. Even the modest distances between planets in our own system are typically measured in years. Our fastest spacecraft would still take well over one year to reach Mars, the closest planet to our own. Thus, it stands to reason that, should we aspire to become a true spacefaring species, the development of practical, efficient, small-scale fusion technology will be crucial. Indeed, in my novel Pioneers, it is noted that interstellar travel was purely theoretical until the advent of fusion power.

Thus, fusion power has become one of those universal features of science fiction, along with folding space and artificial gravity. Yet, unlike the others, it’s seldom discussed. Few notable works of science fiction go into any detail as to its operation. Star Trek paid it lip service, preferring to focus on the warp drive. Halo says little about it, beyond noting the need for deuterium fuel. And while The Expanse went into some detail, it mostly focused on what could go wrong (which, in fairness, is “plenty”).

Obviously, there are inherent perils associated with detailed explanations of fusion power in fiction. One runs the risk of writing a novel that reads more like a physics text. But, while science fiction readers don’t necessarily need to know how everything works, in hard sci-fi, the writer does. And knowing roughly how a fusion reactor works can help to inject believable details into writing that will pique the reader’s curiosity, and appease the more discerning sci-fi fan.

So, how does a fusion reactor operate?

Fusion Power

There are several types of existing fusion reactors, and the design considered most promising changes frequently. For this piece, we will focus on two designs: the tried-and-true Tokamak, and the more speculative Laser-Inertial Fusion reactor.

The oldest proven fusion rector design is the tokamak. A toroidal structure, the tokamak reactor consists primarily of a tube ringed with trap magnets. These magnets compress a stream of fuel traveling through the torus, exciting it into plasma, which generates heat. This heat is used to convert water into steam, which in turn spins a turbine, thereby generating energy.

The tokamak’s sole advantages are (relative) simplicity and reliability. The plasma stream requires immense power from the trap magnets to maintain, which in turn means power output (if any) is relatively low. As with most fusion reactors, the tokamak typically utilizes a Deuterium-Tritium (D-T) fuel cycle. While tritium is more reactive, making for an easier reaction, it’s also far more radioactive. A tokamak may be capable of taking a deuterium-only (D-D) fuel cycle, but even this relatively cleaner fuel cycle yields tritium as a waste product. Most tokamaks mitigate this waste through the use of lithium tracks: strips of lithium running along the outer edge of the torus. As tritium is heavier than deuterium, over time momentum causes it to move toward the outside of the plasma stream, where the lithium scrubs away excess neutrons. This converts the tritium back into deuterium, which can be channeled back into the system as fuel, but it also produces neutron flux: a form of radiation that is highly toxic to most life and lethal to humans.

So, the tokamak is promising, but far from perfect. What, then, is a better alternative?

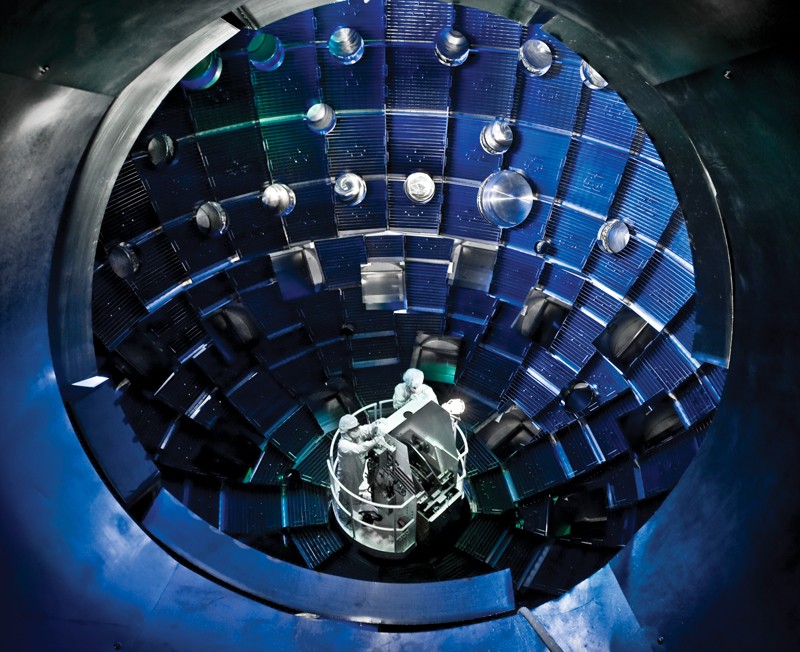

A more recent design is the laser-inertial fusion reactor. In a laser-inertial fusion reactor, a deuterium-tritium pellet (or pure deuterium pellet) is placed inside a containment vessel and bombarded with an ultraviolet laser. This detonates a thin layer of cryogenic deuterium around the outside of the capsule, triggering a process similar to that which occurs within a protostar. The result is, in effect, a miniature sun: a self-containing, self-sustaining fusion reaction. Unlike a tokamak, a laser-inertial reactor would produce energy directly (as opposed to using a turbine). And by immersing the entire containment vessel in molten ceramic, neutron flux can be substantially mitigated.

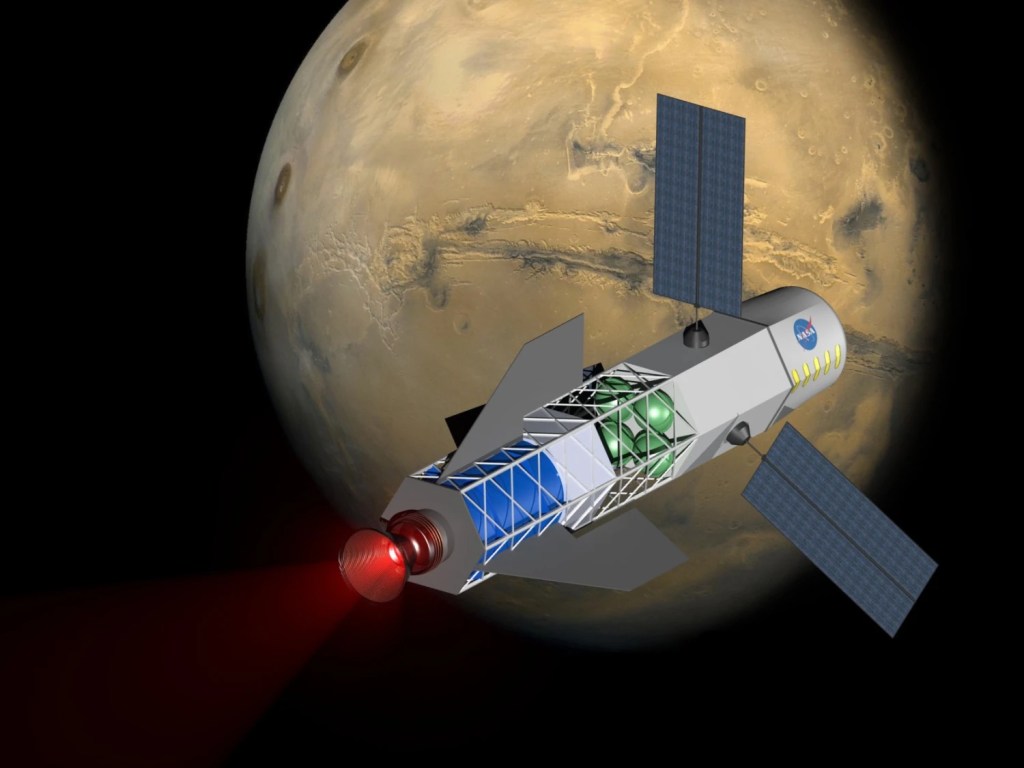

Obviously, all forms of fusion power present serious risks. While fusion reactors do not produce the ionizing radiation most commonly associated with nuclear energy, as stated above they generate serious amounts of neutron flux. The dangers of neutron flux extend beyond its effect on living tissue; radiation from an active reactor could also interfere with the sensitive instruments and other electronics a spacecraft would rely on for everything from communication to navigation. For this reason, many theoretical designs for a fusion-powered spacecraft feature large radiation shields separating the reactor compartment from the rest of the craft.

Still, the benefits are inescapable. Fusion energy, perhaps more so than anything else, is likely the key to humanity becoming a true spacefaring species. The amount of energy required for even practical interplanetary travel, to say nothing of faster-than-light travel between stars, is staggering. Our current mix of photovoltaics and radioisotope thermoelectric generators is simply insufficient to the task. Rest assured, when we finally take our tenuous first steps out into the cosmos, we will do so with the power of the sun. – MK

Am always loving space facts, and while I know next to nothing about physics or actual space info, I do enjoy basking in how small we are in the grand scale of the cosmos. Anyway, thanks for this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry I didn’t notice this sooner, Stuart. Thank you for reading. There will be more “Science In Fiction” posts to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Science in fiction”, love that phrase!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like it! This post was the first in an ongoing series. My next one will be available on Thursday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article. Fusion is almost a requirement for a class 1 civilization.

LikeLiked by 1 person